Biomarkers of Choice in Diagnosing and Following the Course of Neonatal Sepsis, Swedish Data

To map the use of biomarkers nationwide, we conducted an electronic survey aimed towards all neonatal units in Sweden. The goal was to evaluate which biomarkers were in use to diagnose and follow the course of neonatal sepsis, as well as how satisfied the responders were with the diagnostics at hand. Eighty-one percent of neonatal units responded. To diagnose or exclude infection, CRP, high sensitivity CRP, procalcitonin, interleukin-6 and -8 were used, sometimes combined with a complete blood cell count and/or I/T ratio. Each unit used in average 2.4 different tests/patient. To follow the course of sepsis, 1.9 tests/patient were used. A minority of the respondents were completely satisfied with the biomarkers they used, while the majority (83%) found room for improvement. This study could serve as a starting point for improving the use of neonatal sepsis biomarkers. Governmental institutions should benefit from knowing how poorly this is standardized.

Keywords:Neonatal; Sepsis; Biomarkers; Survey; Sweden

Abbreviations:CBC: Complete blood cell count; CRP: C-reactive protein; hsCRP: High sensitive C-reactive protein; IL-6: Interleukin-6; IL-8: Interleukin-8; I/T Ratio: Immature to total neutrophil ratio.; PCT: Procalcitonin; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

Neonatal sepsis is a common and serious condition, which can develop rapidly and cause morbidity or death if not treated properly. In 2018, the Global Burden of Disease estimated the worldwide annual incidence of neonatal sepsis and other infections to 1.3 million cases, or 937 cases per 100 000 live births, leading to 203 000 deaths [1]. Ten per cent of the newborn in Sweden are admitted to a neonatal unit [2], and some 16% of the admitted suffer at least one episode of infection. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare showed in 2014 that sepsis causes about 14% of neonatal death in Sweden [3].

In combination with clinical findings and blood culture, biomarkers are crucial to make the correct diagnose [4]. There is to date no solitary biomarker or combination of biomarkers available for correctly discriminating neonatal sepsis from trauma, tissue damage or even the normal birth process, especially in preterm infants [5-7]. In order to minimize blood loss and to keep costs down, guidelines and consensus would be needed. However, there are no Swedish guidelines for the use of biomarkers for diagnosing and following the course of neonatal sepsis, by either the National Board of Health and Welfare, or the Swedish Society of Neonatology.

In order to investigate the use of biomarkers nationwide, we conducted an electronic survey, consisting of five questions, and asked chief medical officers at all neonatal units in Sweden to participate. The goal was to evaluate which biomarkers were in use to diagnose and to follow the course of neonatal sepsis, aside from blood cultures. Participants were also asked how satisfied they were with the diagnostics used at their unit.

A list of physicians in charge of Sweden’s neonatal units and their e-mail addresses was obtained from the Swedish Neonatal Society. Because of its geographic size, Sweden has no less than 37 neonatal units of varying size and capacity. An anonymized online survey with four multiple choice questions and one open-ended question was created (esMakerNX3, Entergate AB, Halmstad, Sweden). E-mails were sent to the 37 units, containing a link to the survey. The recipients were urged to forward the e-mail to the physician in charge of infectious diseases, if appropriate. A reminder to participate was sent, 21 days after the original e-mail. Participants were allowed 34 days to complete the survey.

After the survey was closed for participation, data was retrieved through esMakerNX3’s website, and exported into Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to create bar graphs and tables.

The entire survey was conducted in Swedish. Translation into English has been done by this study’s authors, including the free text answers.

Out of 35 successfully delivered e-mails, 34 persons opened the survey. Fourteen completed the survey immediately, another 16 after the e-mail reminder, rendering a total response rate of 81%. All 30 responders submitted answers to all five questions.

The first question was “What kind of unit do you reply from?”. Four responders (13%) answered from a tertiary care hospital, 12 from a secondary care hospital with the capability of several days of ventilator care (40%), seven from a secondary care hospital without the capability of several days of ventilator care (23%), six from a primary care hospital (20%), and one stated “other” (3%), which in the free comment section was explained as a tertiary care hospital with the capability of a few days of ventilator care.

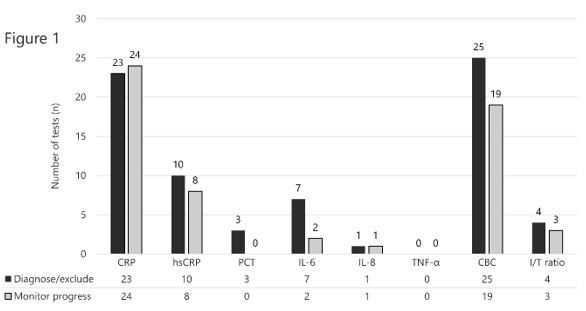

Question two “Which of the following biomarkers does your unit use in daily routine to diagnose/exclude infection?” included a list of the biomarkers we believed to be the most commonly used as answer options, with the possibility of multiple answers if applicable. There was also an option to specify other markers in free text. We specifically pointed out that cultures should not be listed. A total of 73 answers were delivered to this question, including four comments. Twenty-three used CRP, ten used hsCRP, three used PCT, seven used IL-6, six used IL-8, none used TNF-α, 25 used CBC, and four used I/T ratio (Figure 1). Thus, an average of 2.4 different tests per patient. Free text unedited replies: 1. Able to use PCT, more common a couple of years ago; 2. PCT only used for infants that aren’t quite newborn; 3. CRP sensitivity <1; 4. Blood gas (acidosis with no other explanation).

The third question “Which of the following biomarkers does your unit use in daily routine to monitor infection progress during treatment?” was designed as a follow-up question to question two, in order to determine whether the units used the same biomarkers to monitor infection progress as they did to diagnose/exclude infection. The same options were given for answering, again with an option to state other markers in free text. A total of 57 replies were received, with two additional comments. Twenty-four units used CRP, eight used hsCRP, none used PCT, two used IL-6, one used IL-8, none used TNF-α, 19 used CBC, and three used I/T ratio (Figure 1). Free text unedited replies: 1. New CBC for follow-up only if previous tests have shown clearly deviating values (eg severe thrombocytopenia or markedly deviating blood cells/neutropenia); 2. As above (sic!).

Question four “Are you and your unit generally satisfied with the biomarkers you currently use to diagnose/exclude and to monitor infection?” was included to address how content the responders were with the available diagnostic capabilities. Responders were given a choice of four replies, again with the possibility to comment in free text.

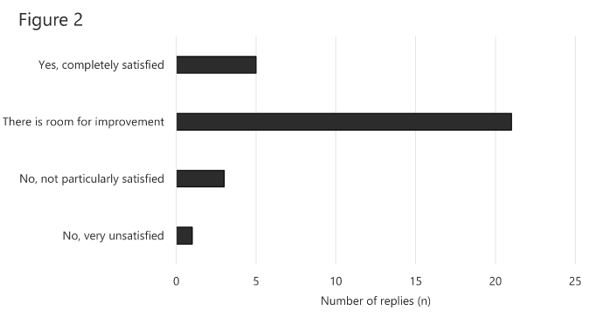

Five persons stated “Yes, completely satisfied” (17%), 21 answered “There is room for improvement” (70%), three stated “No, not particularly satisfied” (10%) and one “No, very unsatisfied” (3%, Figure 2). There were seven comments in free text to this question: 1. A simple blood test with 100% specificity and sensitivity, with 24:7 availability using a minimal amount of blood would have been nice ...; 2. It would be useful to have tests that respond faster than CRP in newborn children; 3. We have discussed IL-6; 4. We want IL-6; 5. Generally overdiagnosis of bacterial diseases and underdiagnosis of viral diseases; 6. Want access to markers that respond faster to infection than CRP!; 7. I’ve read that it is possible to be more specific with more interleukins, for example.

The fifth and final question “Does your unit sometimes use other infection biomarkers than those you use as a routine? If so, which markers and in which context?” was a simple yes or no-question, where we prompted for a reply in free text. Twenty-three (77%) replied that they sometimes did use other biomarkers, while seven (23%) replied that they did not. Free text comments: 1. Some doctors use complete blood cell count in selected patients; 2. E.g. TORCH, some PCR; 3. PCT; 4. PCT - useful to monitor infection progress; 5. Sometimes complete blood cell count is used, but not for routine as such; 6. Possibility of PCT available for use in some cases; 7. GBS antigen.

The response rate (81%) of this short survey is good, indicating that the results should be valid and representative. To our knowledge, no similar survey of neonatal sepsis biomarkers has been published, except a survey of using CRP in neonatal practice [8]. Our results demonstrate a scattered use of neonatal sepsis biomarkers in Sweden, reflecting that there are no guidelines and no consensus. The use of several biomarkers simultaneously – 2.4 on average – is probably due to the fact that there is no solitary biomarker that can be used to safely rule neonatal sepsis out [4]. Our group has previously made a study where we launched the “function of time” concept [9]. When used appropriately, this could help minimize blood sampling. Noteworthy is also the use of interleukins as follow-up blood sample biomarkers. For follow-up, interleukins are of less interest, due to their short serum half-life [10].

Regarding the satisfaction data, we find it remarkable how discontent the respondents are. The majority finds that there is room for improvement, while only a few are completely happy with their practice.

The use of blood sampling that serves little or no purpose, such as using interleukins for follow-up diagnostics, should end, since it causes unnecessary blood loss and is fairly costly. Being a small country with good economic resources and great adherence to guidelines, all neonatal units have excellent possibilities to use the same cutting edge diagnostics. Governmental institutions such as the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare as well as the Swedish Society of Neonatology should benefit from knowing how poorly the use of neonatal sepsis biomarkers is standardized, and preferably act by publishing guidelines. In 2009, the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU) published an “SBU Assessment” on the subject of neonatal hypothermia treatment, where evidence was graded, and therapeutic guidelines suggested [11], causing all Swedish neonatal units using hypothermia treatment to work in the same manner.

We suggest that something similar is done in the field of neonatal sepsis biomarkers. The present study can serve as a starting point for this standardization work. National guidelines in this field are important, since using best practice neonatal sepsis biomarkers are key to optimal antibiotic treatment.

All funding for this project was granted by Futurum research council, Region Jönköping County, Sweden. Futurum research council has had no role in preparing the data or the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.