Congenital Esophageal Stenosis due to Tracheobronchial Remnants: A Case Report

Congenital esophageal stenosis (CES) is a rare anomaly and etiology, with an incidence estimated at 1 per 25,000 to 50,000 live births. Congenital esophageal stenosis is due to either fibro muscular thickening, tracheobronchial remnants or membranous web. Congenital esophageal stenosis due to tracheobronchial remnants is most often located in the lower third of the esophagus and normally begins to show symptoms by the time when solids are added to the diet and endoscopic dilations are usually not successful and may even bare the risk of penetration of the esophageal wall.

We present a case of a 1½ year old girl with a clinical history after surgery of malformations of the heart and a bronchus suis which presented with recurrent laryngotracheal aspirations. After peroral contrast agent supported chest X-ray a long filiform stenosis with all signs of an achalasia was discovered. Subsequent multiple sessions of endoscopic dilations and additional intramuscular application of botulinum toxin resulted in a recurrent stenosis and thus were unsuccessful. After resection of the stenotic part and histopathological evaluation trachebronchial remnants with cartilague within the esophageal wall were found to cause the stenosis.

Keywords: Congenital esophageal stenosis; tracheobronchial remnants

Common etiologies for esophageal stenosis are achalasia, peptic esophageal stenosis due to gastroesophageal reflux and herpetic esophageal stenosis [1,2]. However, CES is a rare anomaly and etiology, with an incidence estimated at 1 per 25,000 to 50,000 livebirths [3]. The first report of CES was published by Frey and Duschl, in 1936. The authors described the case of a 19-year-old girl, whose death was attributed to the diagnosis of achalasia and who was found to have cartilage in the cardia [4]. The classification of CES has been confusing mainly because of its infrequency. Various classifications of CES have been proposed to date. Nihoul-Fékété (1989) clearly defined CES and categorized the cases based on three entities following an approach of Sneed (1979) [1,2]. This categorization has been broadly accepted to date. He claims/determines that CES is either due to fibromuscular thickening, tracheobronchial remnants (TBR) or membranous web. Fibromuscular thickening is found to be the most frequent of these entities followed by TBR and membranous web [3]. TBR are often encircling cartilaginous rings within the wall of the esophagus. Therefore, it is vital to distinguish between these categories because CES due to TBR may only be treated by surgery while the others are often successfully managed by endoscopic techniques [3]. CES due to TBR is most often located in the lower third of the esophagus and normally begins to show symptoms by the time when solids are added to the diet [5].

We report on a 1½ year old girl (twin) delivered by elective ceasarian section because of intrauterine growth retardation in a tertiary care hospital (SSW36+0, birth weight of 1.465g). The postpartal respiratory adaptation was well, she was prenatally diagnosed with Case suspicion of atrioventricular septal defect. The girl suffered from recurrent acute cyanotic episodes associated with dyspnea. She refused to drink and showed clinical signs of heart insufficiency. Enteral feeding was only possible via nasogastric tube..

At the age of three month she developed severe signs of heart insufficiency. Echocardiography revealed a hemodynamically relevant perimembranous VSD (ventricular-septal defect) of 8 mm with bidirectional shunt flow and an ostium secundum ASD (atrial-septal defect) of 10 mm. Heart surgeries was performed in our clinic with patch closure of VSD and ASD.

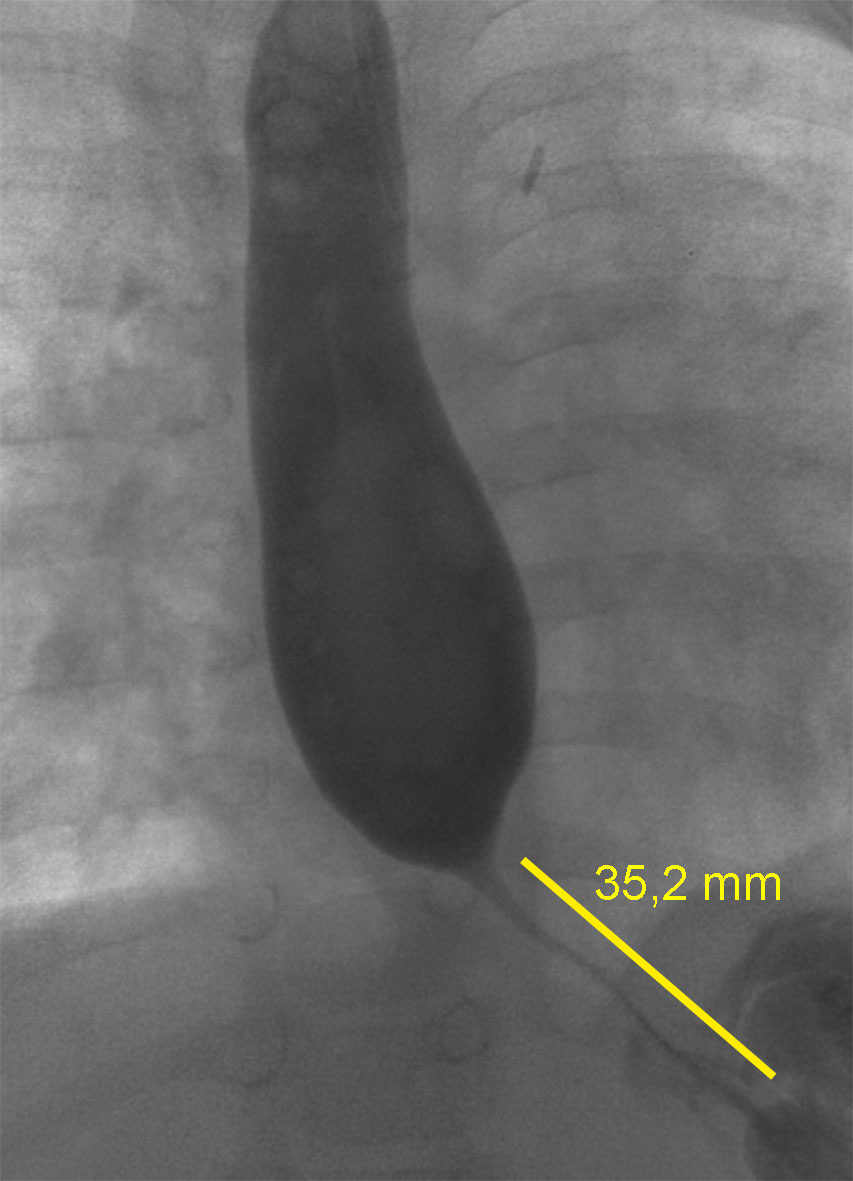

Two weeks later, she was transferred back to hospital because she continuously refused oral nutrition and was still dependent on nasogastric tube feeding. Almost every meal was regurgitated and vomited. In addition, she suffered from recurrent bronchial and pulmonary infections almost every month starting at five months of age. Therefore, she received bronchoscopy and a right bronchus suis leading to the upper right lung lobe was detected. A persisting pulmonary hypertension was diagnosed. The reason for the persisting pulmonary hypertension was found to be due to a chronic interstitial lung disease caused by the recurrent pneumonic infections or laryngotracheal aspirations. To evaluate recurrent laryngotracheal aspirations, contrast agent was applied via the nasogastric tube. A gastroesophageal reflux could be excluded. Further findings were a normal anatomy and passage time without signs of malformation, stenosis or impaired motility. Next, a pediatric gastroenterologist was consulted and it was decided to perform an esophagogastroduodenoscopy. An impassable stenosis was observed at 22 cm and subsequently balloon catheter dilation up to 12 mm in diameter was performed. A peroral contrast agent supported chest X-ray showed a long filiform stenosis (2-3 cm) exhibiting all signs of an achalasia ( Figure 1). Three subsequent endoscopic dilations were performed, all of them with additional intramuscular application of Botulinum toxin. All of them resulted in a recurrent stenosis and thus were unsuccessful. Therefore, at an age of 25 months she received an excision of the stenotic esophageal segment followed by an end-to-end anastomosis accompanied by a gastric transposition / gastric pull-up.

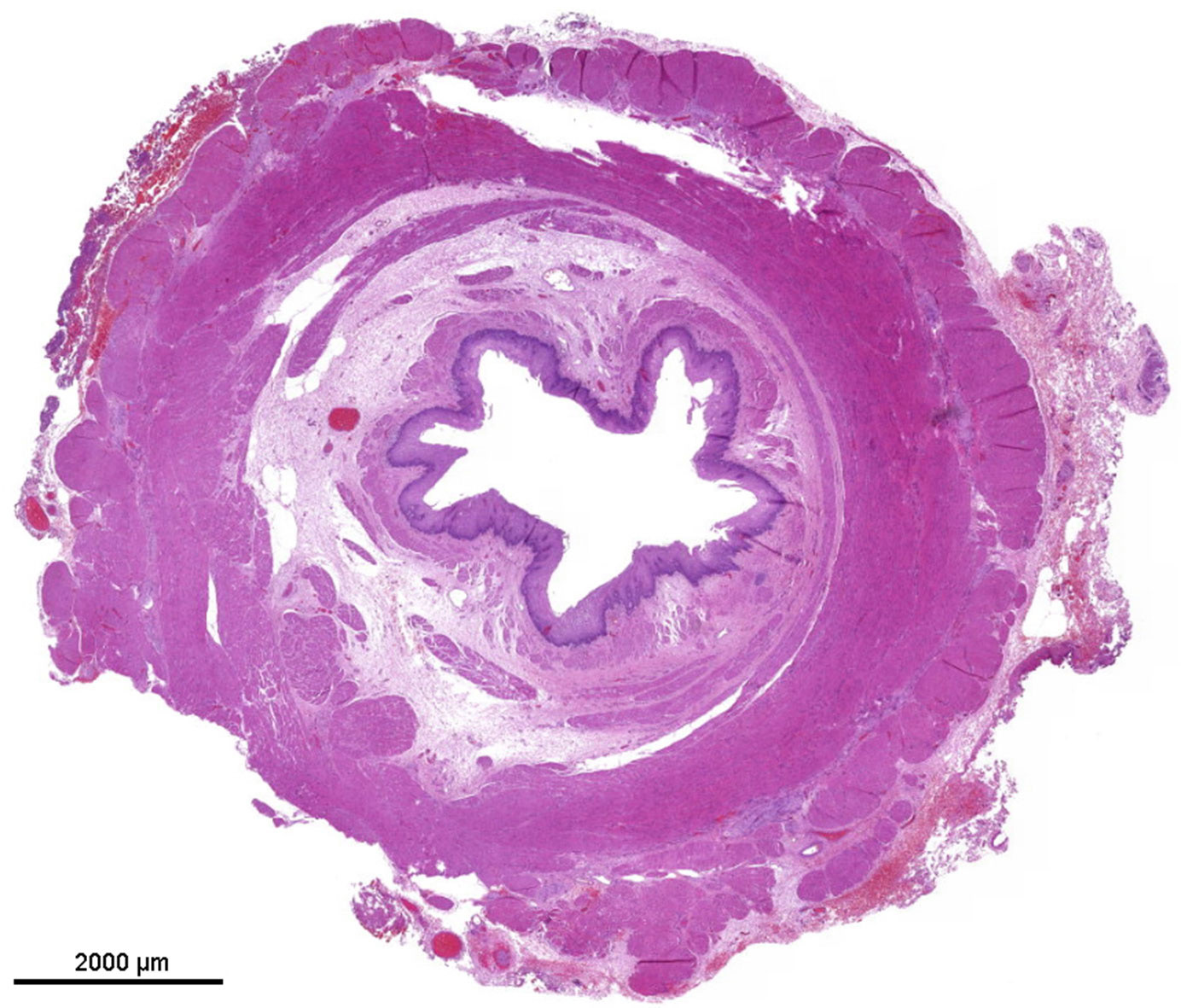

The specimen consisted of a segment of the esophagus of 2, 6 cm in length, narrowed in its central part to a minimum internal diameter of 0, 3 cm and a maximum diameter of 0, 8 cm.

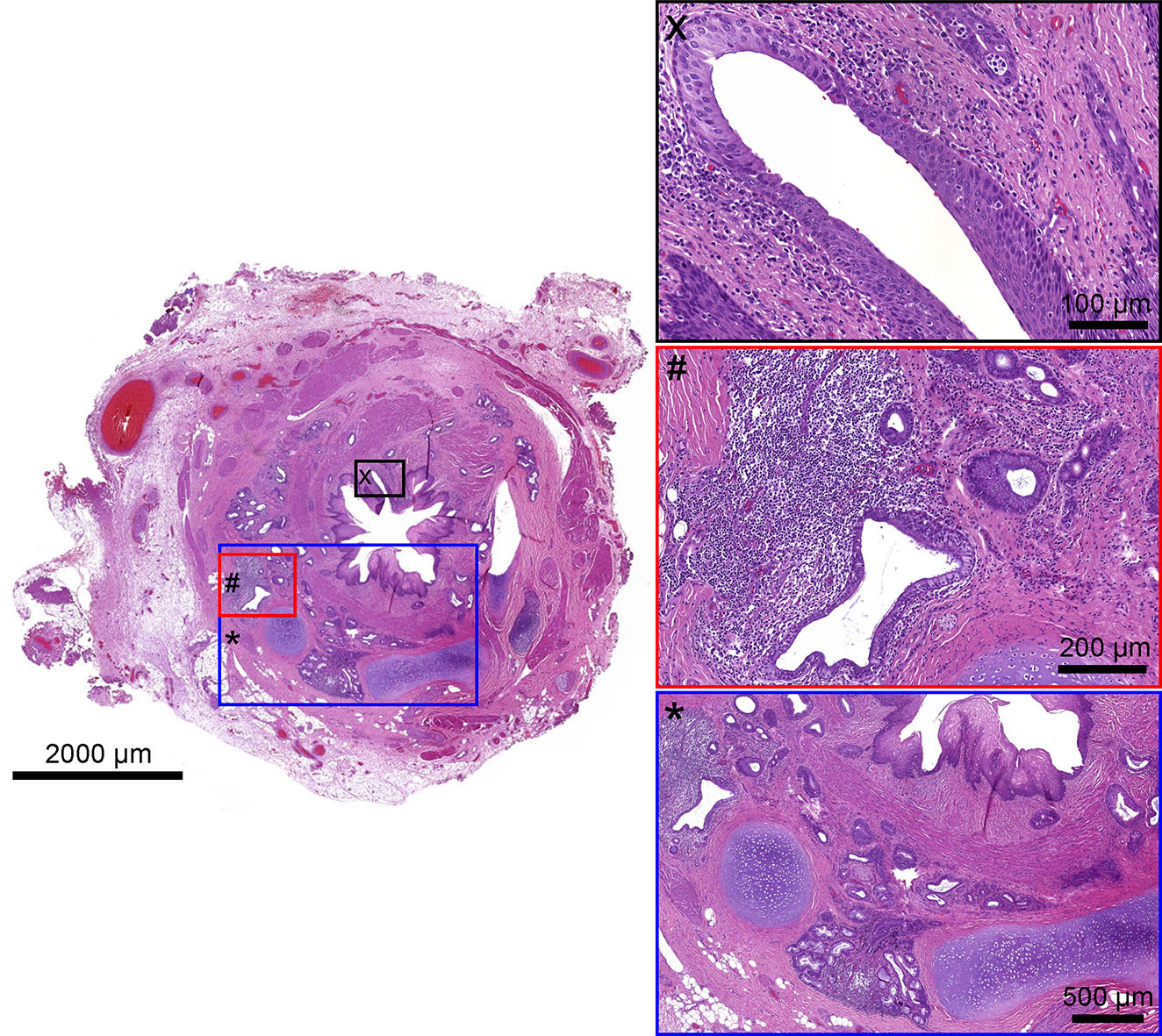

The upper part of the esophagus appeared almost normal (Figure 2). The stenotic part of the esophagus however was lined by pseudostratified columnar ciliated and normally stratified squamous epithelium. Within the submucosa, there were plates of hyaline cartilage and sero-mucinous glands. Associated with the glands were some small cysts lined by columnar epithelium, sometimes pseudo-stratified and ciliated, and surrounded by a lymphocytic infiltrate. The architecture of the muscularis propria was disrupted and no distinct longitudinal or circular layer could be found. Instead, the smooth muscle bundles formed an irregular and discontinuous layer. Taken together the ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium and hyaline cartilage plates as well as sero-mucinous glands are typical for the tracheal wall ( Figure 3). Below the zone of stenosis the esophagus appeared almost normal, with mild submucosal fibrosis and thickening of the muscularis propria.

Embryologically, the trachea and upper alimentary tract have a common origin from the embryonic foregut. In the developing embryo, the tracheobronchial groove, which forms the respiratory system, arises at about the middle to the end of the fourth week as a median ventral diverticulum of the foregut. Two models of development exist: The “septation model” and the ‘tracheal Discussionoutgrowth’ hypothesis. Although clear evidence of a septation is lacking in human embryos [6] it is considered the most likely theory [7]. Separation occurs in the human embryo between Carnegie stages 13 and 16 (28–37 days post-fertilization). By the second intrauterine month, the trachea has differentiated [8,9]Failures of the separation process of the two organs may result in the following ( Table 1):

In most cases, the main feature is the presence of heterotopic respiratory elements such as cartilage and sero-mucinous glands, which is probably a result of sequestration of tracheobronchial mesenchymal cells into the esophageal wall. If these tracheobronchial remnants are small as compared to the caliber of the esophagus, the cause of obstruction might just be an interruption of peristalsis. However, if the cartilage is as large as a cartilaginous ring i.e., this might result in a mechanical obstruction

The distal location of the heterotopic tissue in case of TBR is explainable, by the different growth rates of the tracheobronchial system and the esophagus, which has a greater and faster caudal growth.

The ciliated columnar epithelium present in parts of the narrowed segment in our case and in other published cases [2,14,16,24] probably / possibly represents a localized developmental arrest, because the endodermal epithelial lining of the primitive esophagus in the early stages of development consists of columnar cells, many of whom are ciliated. However, the columnar ciliated epithelium lining structures situated deeply within the esophageal wall are most likely truly heterotopic. In addition, in our as well as in other reported cases the stratified columnar cilated epithelium was partly surrounded by lymphoid tissue [21,25]. In another publication, the authors found a kind of lymphepithelial tissue [21]. The authors presumed that mesenchymal cells, which form cartilage and become sequestrated into the esophageal wall, cause a localized arrest of development in the esophageal epithelium and then could induce the formation of the lymphepithelial tissue. In some cases, the lympho-epithelial tissue was presumably bulky enough to contribute to the stenosis of the esophagus. Indeed, esophageal stenosis due only to this lymphepithelial tissue was reported by Bergmann in 1958 and Spatha in 1959 [26] and none of their specimens contained cartilage.

In the majority of the reported cases, esophageal stenosis associated with tracheobronchial structures is the only congenital anomaly found but other malformations have to be considered. Reports of co-existence of distal esophageal obstruction with esophageal atresia and associated tracheo-esophageal fistula are most frequent [29] [3,30,31]. Other malformations such as duplication of the esophagus, diverticulum and achalasia were also reported [21,32]. Relatively frequent anomalies associated with these findings are congenital heart disease, trisomy 21, anorectal anomaly, duodenal atresia, tracheomalacia and esophageal hiatal hernia [1].

Patients presenting with dysphagia and achalasia symptoms which begin to show by the time when solids are added to the diet and endoscopic evaluation reveals distal esophageal stenosis a tracheobronchial remnant should be considered because endoscopic dilations are usually not successful and may even bare the risk of penetration of the esophageal wall. In addition patients with idiopathic respiratory issues should be considered to undergo early upper gastrointestinal contrast study.