Intradialytic Hypertension and Mortality Risk Among Hemodialysis Patients in The National Kidney Transplant Institute

Background: Hypertension is prevalent in hemodialysis patients and contributes to mortality

Methods: Blood pressures before and after dialysis were used to classify patients (N = 153). Patients were followed for up to 2 years or until death.

Result: Intradialytic hypertension group (n=47) had higher change in systolic blood pressure (16.4 vs – 3.2 mmg Hg) and post dialysis systolic (165.2 vs 147.5 mm Hg) compared to 106 patients without intradialytic hypertension. One and two year overall cumulative survival of patients with intradialytic hypertension compared to patients without were 95.1% vs 92.86% and 66.12% vs 63.03%, respectively. Risk for all cause mortality was non-significantly lower with intradialytic hypertension (HR = 0.98, p = 0.271), female (HR = 0.77, p = 0.495) and calcium channel blockers usage (HR = 0.764, p = 0.46).

Conclusion: In this South East Asian national referral center, intradialytic hypertension did not increase the hazard for 2 years all-cause mortality of hemodialysis patients.

Keywords: Blood Pressure, Cardiovascular Death, Hemodialysis

Hypertension (HTN) is a leading cause of mortality worldwide. [1, 2] It is highly prevalent in patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) and contributes to the high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in these patients. [3] Because the prevalence of HTN among maintenance dialysis patients is 60–90%, its treatment is considered an important means to improve outcomes. [4-6]

The relationship between HTN and cardiovascular mortality in end stage renal disease (ESRD) patients is complicated because of the high prevalence of comorbid conditions and underlying vascular pathology. HTN as a contributor to these cardiovascular deaths has long been recognized in HD patients and majority have poorly controlled blood pressure, at least in part due to the lack of clear guidelines for treatment. [7,8]

Hemodialysis lowers the blood pressure (BP) in most hypertensive ESRD patients but some patients exhibit a paradoxical increase in BP during HD. This increase in BP during HD, termed intradialytic HTN, has been recognized for many decades. [9,10] However, no standard definition of intradialytic HTN exists, it is often under recognized, the pathophysiology is poorly understood, and the clinical consequences have only recently been investigated. [11-13] The occurrence of an increase in BP pre- to post-dialysis has been identified in up to 15% among maintenance HD patients and typically result in post-dialysis HTN. While no consensus definition exists, a consistent increase in BP during HD which results in an elevated post-dialysis BP of >130/80 mm Hg has been proposed to indicate intradialytic HTN. [14]

Recent studies on the prognostic significance of intradialytic BP changes in non-Asian chronic hemodialysis patients showed that intradialytic HTN was associated with adverse clinical outcomes.[14-20] A study done by Inrig et al, showed that patients whose systolic BP rose with HD or whose systolic BP failed to lower from pre- to post-dialysis had a 2-fold adjusted increased odds of hospitalization or death at 6-months compared to patients whose systolic BP fell with HD.[14] Some studies have identified pre-dialysis systolic BP to have an inverse association with mortality.[15, 16] In addition, increased post-dialysis systolic BP has been noted to be associated with adverse outcomes.[19]

Conflicting literature reviews and opinions confuse the practicing physician on which BP to treat: pre-dialysis, post-dialysis or combination of both. This study attempted to evaluate our South East Asian experience to inform our medical colleagues regarding the validity and applicability of observations in non-Asian occidental populations to this part of the world.

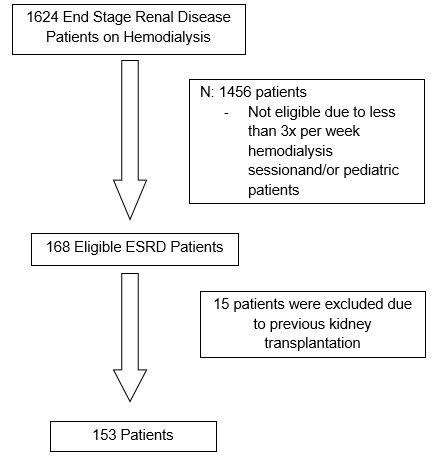

The study was designed to determine the association between intradialytic hypertension and mortality among hemodialysis patients at the Philippines’ National Kidney and Transplant Institute (NKTI). All adult (age ≥18 years) maintenance HD patients surviving at least the first 60 days of dialysis and treated by 3x/week hemodialysis for more than 4 weeks at NKTI from January 1, 2011 to December 31, 2013 were included. Patients who previously underwent kidney transplantation were excluded from the analysis. The patient entry into the study cohort is illustrated in Figure 1. Clinical data was reviewed and collected by the investigator from the NKTI-Hemodialysis Unit and Medical Records. These include demographic features and clinical parameters such as age, gender, primary renal disease, comorbidities, medications, anemia management, and serum biochemical data. Blood pressures were routinely collected and electronically recorded within the database. Hemodialysis blood pressures during hospital admissions were excluded. Twenty-four consecutive pre – and post-dialysis blood pressures prior to study start date were included and the difference between each treatment’s pre and post were averaged across all treatments. Intradialytic hypertension was considered if patients average change in systolic BP (SBP) increased by more than 10 mm Hg. For descriptive purposes, patients were categorized into 2 groups based on Δ SBP: presence of intradialytic hypertension and absence of intradialytic hypertension. Interdialytic weight gain was calculated as the average change in weight between dialysis sessions. Antihypertensive medications were grouped into the following classes: angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-i), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), alpha and beta blockers, calcium channel blockers (dihydropyridine and nondihydropryidine), central acting (clonidine), and vasodilators (hydralazine). Erythropoietin stimulating agents were presented as per week usage to maintain an acceptable hemoglobin level.

• Mean arterial pressure (MAP) was calculated as [(2 × diastolic BP) + systolic BP]/3

• The difference between pre- and post-dialysis SBP (Δ SBP) was calculated as post-dialysis minus pre-dialysis BP.

• The change in systolic blood pressure was averaged over the 24 consecutive hemodialysis sessions.

• Interdialytic weight gain was computed as the average change in weight between dialysis sessions.

• Coronary artery disease was defined as the presence of prior history of either of the following: myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass grafting, prior angioplasty, and/or abnormal cardiac catheterization

• Cerebrovascular disease was defined as presence of prior stroke or transient ischemic attack.

• Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease was defined as presence of emphysema and/or chronic bronchitis.

• Peripheral vascular disease (PVD) was diagnosed if with an amputation due to PVD, absent foot pulses, or claudication.

• Congestive Heart Failure was defined as complex clinical syndrome that results from structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood, which in turn leads to the cardinal clinical symptoms of dyspnea and fatigue and signs of HF, namely edema and rales

The primary outcome was time to 2-year all-cause mortality. Patients were censored on death, loss to follow - up, transplant, and transfer to another institution or at the end of the study period (December 31, 2015). A secondary endpoint was cardiovascular mortality.

Values of the continuous variables were presented as mean and standard deviation and values for categorical variables were presented as numerical count and percentage. Pearson Chi-Square test for Comparison of Proportions and Mann – Whitney Test was used for comparison of means as appropriate. Cox proportional hazards models were used to determine the significance of variables in predicting the primary end-point, all-cause mortality. Variables associated with clinical outcomes were analyzed with univariate Cox regression analysis. Kaplan-Meier analysis was used to assess the difference among patients with – and without intradialytic hypertension in reaching the primary end-point. SPSS version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All probabilities were two-tailed and a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Confidentiality of the subjects was maintained. Only the principal investigator and co-investigator accessed the patient’s database. Anonymity was ensured and each patient was assigned with a case number. Other identifying information was not essential to the study and was not collected. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee of National Kidney Transplant Institute.

A total of 153 HD patients were included in the study with demographic characteristics shown in Table 1. At enrolment, male predominance was evident (52%) with mean age of 59.3 years old. Majority had Diabetic Nephropathy (48.4%) as primary renal disease, followed by Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis (28.1%) and Chronic Glomerulonephritis (18.3%). Most patients had 1 – 2 comorbidities with 72.1% having Diabetes Mellitus, 27.9 % with coronary artery disease and 26.9 % with congestive heart failure. Fifteen out of 153 patients (9.8%) had a prior history of malignancy, namely: colon, lung, thyroid and renal cell carcinoma.

Forty-seven (31%) patients had intradialytic hypertension as defined by change in SBP > 10 mm Hg and 106 (69%) patients did not display intradialytic hypertension. Majority of patients with intradialytic hypertension had Diabetic nephropathy (42.6%) as primary renal disease and had diabetes (73.1%) and coronary artery disease (26.9%), but were not significantly different to patients without intradialytic hypertension (p value > 0.05). There were significantly more female patients with intradialytic hypertension (64%) in comparison to patients without (41% p = 0.011).

Patients with intradialytic hypertension had significantly greater change in systolic blood pressure (+16.4 vs –3.2 mmHg), post dialysis systolic blood pressure (165.2 vs 147.5 mmHg) and mean arterial blood pressure (106 vs 97.8 mmHg) compared to those without intradialytic hypertension, (p value < 0.05). Mean dialysis weight gain were 2.5 kg and 2.4 kg in patients with - and without intradialytic hypertension, respectively. Two to three anti – hypertensive medications were used to control blood pressure for both groups. Calcium channel blockers (73.4%), Angiotensin receptor blockers (48.9%), and Beta blockers (46%) were commonly prescribed. Calcium channel blocker were significantly prescribed to patients with intradialytic hypertension compared to those without hypertension (p value of 0.035)

Dialysis vintage of both groups were not significantly different. Most of the population had a year on hemodialysis prior to the study. Hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, calcium, phosphorus and erythropoietin stimulating agent usage were not significantly different in both groups (p value > 0.05).

Table 2 shows the outcome of the hemodialysis patients. By the censor date, 31 patients (20.3%) had died of whom 22 (71%) were related to cardiovascular etiologies. Causes were acute myocardial infarction for 21 patients and malignant arrhythmia for 1 patient. Sixty-four were censored due to lost to follow up/transfer to another hemodialysis unit (n=43) or underwent kidney transplantation (n= 21). Censored patients were similarly distributed for both groups. Intradialytic hypertension group had 9 deaths (19.1%) in comparison to 22 (20.8%) deaths of non – intradialytic hypertension group. Cardiovascular cause mortality accounts for 19.4% and 51.8% deaths of patients with and without intradialytic hypertension. Other mortalities were attributed to sepsis secondary to pneumonia. No withdrawal from hemodialysis was noted.

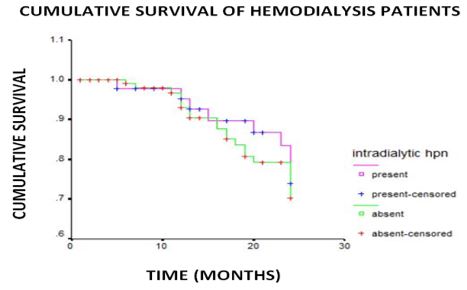

Comparison of the overall survival of patients in terms of intradialytic hypertension was shown in Figure 2. One and two year overall cumulative survival of patients with intradialytic hypertension compared to patients without were 95.1% vs 92.86% and 66.12% vs 63.03%, respectively. Mean survival time of patients with intradialytic hypertension was not significantly different to patients without (22.56 vs 22.06 months; log rank 0.22 p value 0.64).

Among the factors observed, female gender, change of systolic blood pressure > 10 mmHg, higher post dialysis systolic and mean arterial blood pressure and use of calcium channel blocker were the factors affecting the 2 year survival of patients. Cox regression analysis of these factors was shown in Table 3. An insignificant increase in risk for death if patient had elevated post dialysis systolic and mean arterial pressure (HR = 1.01 p value of greater than 0.05) compared to patients without was observed. Lower risk of dying if patient was female (HR = 0.77 p = 0.49), had intradialytic hypertension (HR = 0.98 p = 0.27) and use calcium channel blocker (HR = 0.76 p = 0.46) was identified.

In the present study, we examined the association between intradialytic hypertension and mortality, with the former defined by intradialytic change in systolic blood pressure that is greater than 10 mmHg. The mean change in systolic blood pressure of our patients with intradialytic hypertension was 16.4 (+4.58) mmHg. The prevalence of intradialytic hypertension in National Kidney Transplant Institute is higher (31%) compared to other institutions (10 – 15%). [15] The study was unable to detect an increase in hazard (HR = 0.98, p value of 0.271) for all-cause mortality over 2 years for patients with intradialytic hypertension. In a previous report involving 443 participants, patients whose post dialysis SBP increased were observed to exhibit a 2.17 fold increased adjusted odds of the composite outcome of non-access related hospitalization or death after 6 months of follow-up. For every 1 mm-Hg increase in change in systolic blood pressure following dialysis there was a 2% increased odds of non-access-related hospitalization or death. [10] Secondary analysis comprising of 1,748 participants showed 12.2% patients had a greater than 10-mm Hg increases in SBP during hemodialysis. It also detected a 6 % increase in the adjusted hazard for death over 2 years for every 10 mm Hg increase in SBP during dialysis. [11] A prospective cohort encompassing 115 patients from Taipei Veterans General Hospital noticed 39 patients with average postdialysis SBP rise of more than 5 mmHg. They were observed to have highest risk of both cardiovascular and all-cause mortality compared to others. [19] Another retrospective study of 113,255 hemodialysis patients noticed a U-shaped association between change systolic BP and all-cause mortality in which large decreases (about −45 mmHg) and increase (about – 5 mmHg) in systolic BP during HD were both associated with increased mortality. [20] In comparison to the previous studies, we were not able to detect such association. It is possible that our study population was different. In the current cohort, patients with IHD were younger, with female predominance; fewer patients in our total cohort had congestive heart failure, had dialysis vintage of less than 1 year and generally had less change in systolic blood pressure. It is unclear if the small sample size of the study may have precluded detecting a significant difference.

Previous reports indicated that hemodialysis blood pressures recorded from 3 – 6 sessions was poorly correlated with end organ damage and cardiovascular outcome. [19] Prior cohorts derived their results from 3 – 6 sessions only, while the present results came from the mean values of BP recorded for 2 months. As suggested, the average pre-dialysis systolic BP taken for more than 1 month may be equally representative of the true BP than 24 hour ambulatory BP monitoring. Our study may therefore reflect the actual post-dialysis BP alterations in hemodialysis patients.

There are emerging mechanisms that may explain the causes of post dialysis hypertension. Hypervolemia is a well-recognized risk factor for hypertension among HD patients and is the cause of intradialytic hypertension in a subset of patients identified in the study of Yang et al. [19] Other known plausible contributors of post dialysis hypertension are sympathetic nervous system over activity, RAAS activation and endothelial cell dysfunction. In this study, the interdialytic weight gain (IDWG) of the patients is more than 2 liters which might indicate hypervolemia as the cause of hypertension.

All classes of antihypertensive drugs, except diuretics, are useful for managing hypertension in hemodialysis patients.[21-23] Among all classes, calcium channel blockers are the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive agents and offer the advantage of not being cleared during hemodialysis.[24] Calcium channel blockers have been reported in some studies to lower the risk of mortality in hemodialysis patients.[24-25] In present study, the use of calcium channel blockers trended albeit without reaching statistical significance, to associate with a lower risk of death in hemodialysis patients.

The study has several limitations: First, the study design was observational and non-randomized in nature. Second, the small sample size and a relatively high censor rate from lost to follow-up may have affected power to detect differences even if they were truly present– however, the smaller Taiwanese study detected an association between IDH and mortality even with only 115 patients. [19]

In this South East Asian national referral center experience, intradialytic hypertension and mortality was not associated with all-cause mortality over 2 years follow-up for maintenance hemodialysis patients. Pathogenesis of intradialytic hypertension and identification of patients susceptible to worse outcome must be determined for appropriate triage of management and formulation of specific interventions of this condition.

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.