Making Healthcare Waste Management a Priority: The Reality of Solid Waste Disposal at an Urban Referral Hospital in Uganda

Background: There are significant gaps in healthcare waste management (HCWM) in many developing countries. Poor HCWM practices potentially expose patients, medical personnel, waste handlers and the community to major occupational, environmental and public health risks. HCWM practices at referral hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa have not been described previously.

Methods: We reviewed cross-sectional qualitative data at Kiruddu Referral Hospital, Kiruddu, a large urban hospital, between August 2018 and December 2018 with the primary aim of assessing current procedures and practices of handling medical waste.

Results: There was a general lack of systematic guidelines and principles which were important factors contributing to suboptimal HCWM.

Conclusion: Emphasis by the hospital authorities should be focused on institutional and operational guidelines, capacity building and adoption of environmentally and economically sound HCWM approaches.

Keywords: Healthcare Waste Management; Developing Countries; Hazardous Waste

On a global scale, medical waste generally represents a small percentage of total generated waste. Nonetheless, up to 25% percent of this medical waste is hazardous/infectious and therefore is of concern because of the environmental hazards and public health risks that this waste carries [1,2]. Over the past decade, Kampala district, which is the capital city of Uganda, has experienced a significant upsurge in the number of both public and private healthcare establishments with a 15% increment from 4,450 facilities in 2010 to 5,117 facilities in 2016 [3].

This coupled with the increased population growth and the adoption of disposable medical products has inevitably contributed to significant increases in healthcare waste (HCW) [4,5]. It is also crucial to note that there’s evidence that suggests that recent incidence rises of HIV, Hepatitis B and C have been attributed to waste handlers, on the account that 40% of waste being handled by waste handlers is hazardous [6].

In developing countries, especially sub-Saharan Africa, not only has the field of HCWM generally received insufficient attention and interest but there’s a general paucity of data in this regard [7]. Current evidence in HCW research in hospitals in Africa has only been extensively conducted in Ethiopia and Nigeria [8-15].

Typically, HCWM in Uganda is the responsibility of the national environment protection and conservation agency, the National Environmental Management Authority (NEMA), which is governed by the National Environment Act 1995, Cap 153 and the national environment (Audit) Regulations, 2006 [16,17]. In spite of existing regulations, there is a myriad of challenges including a significant lack of awareness of existing policies, limited technical capacity, ineffective implementation of policies, limited budget allocations, lack of government commitment and insufficient stakeholder participation and linkages [18,19]. The main objective of this study is to assess the current procedures and practices of handling medical waste at the Kiruddu Referral Hospital- Kiruddu.

Kiruddu Referral Hospital-, Kiruddu, is an urban, public hospital located approximately 13 kilometers south-east of the main Mulago National Referral Hospital and has been operational for a little over 28 months. The construction of this hospital is part of government efforts to improve health service delivery because of the rapid expansion of Kampala, the central city’s, population [20]. Kiruddu Referral Hospital- Kiruddu provides both inpatient and outpatient services with an average outpatient turnover of 250 patients daily.

A qualitative observational study at the Kiruddu Referral hospital – Kiruddu was from August 2018 to December 2018. Data was collected in accordance with the Individualized Rapid Assessment Tool (I-RAT), a specified tool developed by the United Nations Development Program Global Environment Facility project that can be utilized to indicate levels of HCWM at healthcare facilities. It can also be used to reduce disease burden attributed to poor HCWM. This is the first study in Uganda to evaluate waste management practices in a public health institution. The findings from this study will be fundamental in devising effective HCWM practices and standards. This study will also seek to make the case for prioritizing HCWM interventions. The measures suggested in this study will be adopted as the benchmark for HCWM in health centers and hospitals countrywide.

The data for this study was collected through the use of oral interviews and regular field visits from August 2018 to December 2018. Discussions were initiated by an open-ended question on the HCWM experiences at the referral hospital. Consent was provided prior to the evaluation. Audiotapes were subsequently transcribed verbatim and qualitative thematic content analysis was conducted by two independent coders: the investigator and a graduate public health student.

Qualitative concepts were generated from the data following the evaluation. The two independent coders read the transcripts line by line and abstracted key ideas and themes.

A total of 42 regular visits which were twice weekly, were performed to monitor how HCWM was practiced. Data were collected regarding waste generation, collection, segregation, storage and transportation on-site. There were no significant differences observed during visits. Seven major themes emerged from the evaluation: (i) policies and guidelines, (ii) medical waste generation, (iii) segregation and collection, (iv) waste handling (v) storage and transportation, (vi) disposal and (vii) safety. Assessment and scores were based on compliance with the Individualized Rapid Assessment Tool (IRAT) (Table 1).

There is neither a HCWM department nor HCWM committee in place to monitor HCWM activities in the hospital. Although the hospital director is aware that there are government rules and regulations pertaining to waste management, the hospital has not developed institutional HCWM policies and standard operating procedures. Training programs related to HCWM, standard operating procedures and legal provisions for waste management, segregation, collection, disposal, safety issues and safe injection practices for patients’ caregivers, physicians, nurses, waste handlers, were non-existent.

Medical waste inventories throughout the hospital are non-existent hence quantitative data pertaining to the amount of medical waste generated was absent. Additional waste statistics indicating source, type and time were also lacking. Pictorial illustrations that would be critical in guiding patients, patients’ caregivers and visitors at waste generation points were non-existent.

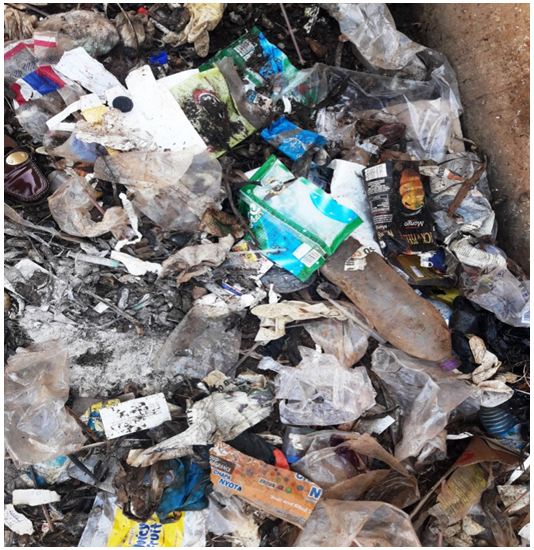

Although waste was generally discarded in large waste bins and sharps in separate sharps containers, the concept of waste segregation was non-existent. Insufficient segregation at waste disposal points resulted in domestic waste being mixed with HCW (Figure 1a,1b and 1c). This will inevitably increase both waste disposal costs and health risks to health workers, waste disposal workers and the public (Figure 1). There was a visible absence of appropriate color coded and labeled waste bins and as a result, the hospital did not follow the recommended WHO basic three-bin system for simple and safe waste segregation system at the points of waste generation (Figure 2) [21].

Posters aimed at reinforcing good waste management practices, indicating the type of waste for instance hazardous vs. non-hazardous waste to be disposed in waste receptacles, placed at appropriate waste generation points for instance on the walls adjacent to these waste receptacles were absent (Figure 2). Furthermore, absence of appropriate labeling, reinforcement and color coding makes identification of the type and source of medical waste difficult for both health workers and the public.

Transportation of waste is done with wheelbarrows. The transport staff was observed to adorn only one form of personal protective equipment (PPE) - gloves. They did not wear the satisfactory PPE – in particular overalls, eye protection, masks, aprons and closed shoes as is recommended by WHO [21]. Because of inadequate color coding and segregation, hazardous and non-hazardous waste is transported as mixed waste.

The hospital neither has a dug-out waste pit nor a medical waste incinerator. There is an on-site temporary waste storage area that was cordoned off under the directive of the hospital director. Although this temporary waste storage area is isolated from the general public, it was initially an open air storage area, making it completely exposed to the elements particularly rain and heat (Figure 3). At the start of the evaluation, in the likelihood of rain, the rainwater that fell on the waste, washed through the waste producing a toxic leachate, that flowed downhill by gravity to the gate and then outside the hospital premises. In the likelihood of high temperatures during the hot season, offensive odors were generated from this waste area which could increase exposure risk to waste workers.

During the course of the evaluation, in December, plans were approved to construct a waste storage area that would address the issue of exposure and the toxic leachate (Figure 4). The storage area is partitioned into two areas is relatively clean and cordoned off from the public.

Final disposal to an off-site area is done by outsourced disposal company trucks which come to the hospital once weekly and in all cases infectious waste is transported together with non-infectious waste. The disposal workers typically do not wear sufficient protective gear for instance, overalls, eye protection and masks hence increasing the potential of health risks. Protection is limited to gloves and boots. Information pertaining to waste composition and mass has not routinely provided to waste handlers.

Mitigation against infectious diseases for physicians, nurses and handlers of medical waste was virtually non-existent. Serological screening for HIV sero-conversion and vaccination against infectious diseases in particular Hepatitis B and tetanus as well as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) against HIV in the event of needle-stick injuries were absent.

This is the first study of its kind in Uganda, documenting that WHO and United Nations Development Program Global Environment Facility guidelines on HCWM are not being followed by the referral hospital in Kiruddu, Kampala a public sector healthcare hospital. With increasing urbanization, most developing countries are facing the growing challenges of healthcare waste management. In Uganda, there are hardly any robust frameworks for operationalizing, institutionalizing and sustaining best practices for HCWM.

HCWM is an essential element of how efficient a hospital and consequently a country’s health system is. The findings from this study reiterate the inefficiency of medical waste management at the Kiruddu referral hospital. The study findings demonstrated that HCWM is not a priority in this referral hospital as evidenced by the lack of allocated budget funding towards waste management and the lack of economical waste management facilities for instance on-site incinerators.

HCWM protocols and regulations in developing countries have generally not been implemented in comparison to developed countries. This effectually shows how inefficient the health systems of developing countries are. Because HCWM is not considered as priority, hardly any funding is allocated and as a result, HCWM policies, protocols, regulations, guidelines and implementation plans in most developing countries are non-existent and ineffective and are still an unmet goal in developing countries.

The pre-intervention evaluation showed poor waste management practices at Kiruddu referral hospital, which is similar to studies in other countries that demonstrate that compliance with HCWM regulations and guidelines in many healthcare facilities remains a challenge.

It is critical to note that one of the common barriers to effective HCWM in health facilities is lack of proper waste management practices among patients and patient caregivers as evidenced in this study by the observed lack of waste segregation at waste generation points [22].

As is seen by the findings in this study, solid waste is not sorted which in turn makes handling hazardous. Because mis-segregated HCW, subsequently, leads to elevation of HCWM costs, implementation of HCW segregation and minimization are therefore crucial to decreasing costs attributed to HCWM. During observations, it was obvious that transportation of hazardous and non-hazardous waste was also not segregated. Inability to separate medical waste from ordinary garbage potentially puts health workers, disposal workers and scavengers at serious risk of contracting HIV/AIDS, tetanus, Hepatitis B and C. There’s compelling evidence that confirms that the prevalence of Hepatitis B and C infections are much higher in healthcare workers and waste-exposed populations in comparison to the general population, thus making them high risk groups [23-26]. Infectious waste increases transmissibility of major bacterial infections particularly salmonella typhi, pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli and staphylococcus aureus [27-30]. These pathogens can lead to the contamination of groundwater and air particularly, E. coli.

It therefore is essential for health institutions to promote vigorous HCWM practices. To counteract the unnecessary health risks of HCWM it ought to be mandatory for health institutions to adopt full PPE for waste disposal workers and health workers (cleaners) as well as availability of annual blood testing, appropriate PEP and mandatory vaccination programs for all waste disposal workers and health workers against hepatitis A and B and tetanus. Positive strides were taken during the course of the evaluation to address the toxic leachate from the previous open air temporary waste storage area to an enclosed spacious waste storage area. It is critical that every hospital and health center have internal waste disposal inventories. A central online manifest system that monitors medical waste transportation is essential to ensure firstly, that infectious medical waste is tracked and secondly that protocols and regulations regarding safe disposal of infectious medical waste are adhered to.

Effective capacity building and training programs incorporating public and private health institutions, waste collection and disposal companies, municipal governments, partners and stakeholders are vital to scaling up implementation of HCWM policies. There’s need for effective visual training aids, health talks, announcements and counseling sessions that equip patient caregivers with proper waste management techniques. This study has limitations. Most studies on HCWM have a quantitative aspect to it. There was no quantitative data because of non-existent health care waste management policies. The other limitation is that this study was restricted to one hospital hence the findings may not be generalizable. Adequate budgetary allocations, adoption of robust HCWM plans and HCWM training at health centers and hospitals should also be prioritized as key to the health policy agenda.

The study has several limitations. Neither cost nor benefits data were available or collected during this study period hence inability to conduct either a cost analysis or a cost-benefit analysis. There is need for cost-benefit research in HCWM to inform policy on the economic benefits of alternative types of HCWM systems for instance non-incineration HCWM vs incineration HCWM. Fundamental costs pertaining to loss of life, lost work days due to occupational related illness, increased health care needs were unable to be estimated because the data was not available.

Due to the limited resources we had in our setting, we were unable to characterize the waste stream in terms of outpatient waste vs inpatient waste. Another limitation is that the study was based on a single-center evaluation (one facility). As much as we sought to illuminate the area of HCWM in health institutions in urban settings in developing countries, the data obtained in our evaluation may not be generalizable to other health institutions in developing countries. Despite these limitations, the study confirms that operationalization of sound HCWM practices in urban referral hospitals in Uganda is generally lacking. Health institutions can expect that a significant proportion of waste handlers, patients, medical personnel and scavengers harbor undiagnosed and untreated Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C and HIV. Health institutions should prioritize adoption of robust HCWM practices and concurrently implement screening, prevention and treating algorithms for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV in these high-risk populations in order to prevent incidence resurgence.

The general observation is that HCWM at Kiruddu referral hospital is poorly-coordinated, under-financed and under-prioritized achieving a score of 5.5% ( Table 1). Due to poor leadership and weak HCWM implementation practices, the institutional framework for HCWM that encompasses policies, surveillance and interventions is virtually non-existent. Compliance of Kiruddu referral hospital with WHO recommendations of immunization and use of PPE for waste handlers and all healthcare workers is important in reducing risks of exposure to infectious diseases. The ramifications of poor HCWM as seen in this study are far-reaching affecting health workers, waste handlers, waste disposal workers, scavengers, the local community and the environment. It is crucial for health institutions, to establish occupational medical departments that are dedicated to effectively governing generation of medical waste. It is also critical to note that training and capacity building are the cornerstones to effective HCWM.

Adoption of environmentally and economically sound HCWM approaches for instance installation of an incinerator and autoclaves will go a long way in counteracting the effect of hazardous waste and toxic leachate at Kiruddu referral hospital.

The author provides the following recommendations as a way forward towards effective and sustainable HCWM:

1. Formulation of an appropriate institutional HCWM plan and HCW SOPs.

2. Creation of an occupational health and safety department that will monitor HCWM activities and provide appropriate vaccination for tetanus, Hepatitis B and PEP for HIV.

3. Prioritization of HCWM in order to provide for job creation, improved service delivery, cost reduction and revenue generation.

4. Budgetary allocation for HCWM.

5. Prioritizing HCWM activities and research.

6. Regular staff training and capacity building.

7. Information, Education and Communication (IEC) of HCWM practices to hospital staff, waste handlers, waste disposal workers, patients and patients caretakers.

8. Prioritizing HCWM strategies for instance use of multi-chamber incinerators and adoption of alternative modern technologies to treat HCW for instance autoclaves and shredders.

I accord double honor to the chief custodian of this project, Prophet Elvis Mbonye to whom I am entirely indebted. I would like to thank the Director of Kiruddu referral hospital, Dr. Charles Kabugo for his invaluable collaboration and support during this study.