Medico-Legal Implications of Assessing and Treating the Aftermath of Trauma

A case involving a road traffic accident resulting in severe personal injuries was illustrated in the context of the medico-legal trail towards compensation. Key clinical and medico-legal issues were considered and described in the context of Koch’s postulates. The progressive, logical and comprehensive medico-legal understanding of trauma and its implications for a more ‘therapeutic jurisprudence’ approach to civil cases is discussed.

Keywords: Road traffic Accident; Medico-Legal Trail; Diagnosis; Prognosis; Causation; Reliability; Therapeutic Jurisprudence

List of Abbreviations: CBT: Cognitive behavioural therapy; GAD: Generalized anxiety disorder; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; NICE: The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

The development of innovative medico-legal commentary for exploring the interface between clinical opinions and legal issues in UK civil and criminal litigation was initiated in 2016, outlining a process of documenting psychologically-relevant commentaries for civil case litigation [1]. This paper describes in legal and clinical detail how one particular application for compensation in the UK courts (in 2015) reflected medico-legal and clinical considerations. The individual claimant concerned is anonymised. As both DSM IV and DSM V classification schemes were in use at this time, both sets of diagnostic coding are given [2,3].

Mrs C was a 31-year-old who was a front seat passenger in a car driven on a motorway by a work colleague in the Manchester area (UK). The colleague fell asleep and the car hit the central reservation before spinning around and overturning. She did not lose consciousness but was dazed and shocked. She had a momentary thought that she was about to die. She was taken to hospital where physical injuries in her neck, back, and left side were diagnosed. She was a public-sector worker. She had several months off work due initially to physical pain and subsequently due to anxiety and low mood.

Mrs C had an initial assessment by a psychologist expert instructed by the claimant solicitors at approximately 6 months post-trauma. He identified psychological symptoms of stress, mood disturbance, travel fear and avoidance and social withdrawal. He recommended Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (8-10 sessions) which was provided. Thirty months later, he reassessed her to review the effect of the treatment, and found a partial improvement in her psychological symptoms. Treatment notes seen indicated she had ‘extreme difficulty in reducing her safety behaviour and avoidance behaviour’. She had still been unable to return to her job, partly, in her opinion, due to travel avoidance. Two psychometric tests were given. The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 [4]. Anxiety scale and the PHQ -9 Depression Scale [5]. These tests are widely used in assessing post-accident trauma and stress (Graph 1).

This test data is a ‘secondary’ source of information.

These tests are used as screening tests, not as diagnostic instruments. They were used in this case to assess change over time. This data may ‘point to’ the existence of a particular disorder and may guide the interviewer to ask more detailed questions designed to detect this disorder. The data in this particular case was consistent with a reduction in anxiety and depressive symptoms between the two assessments.

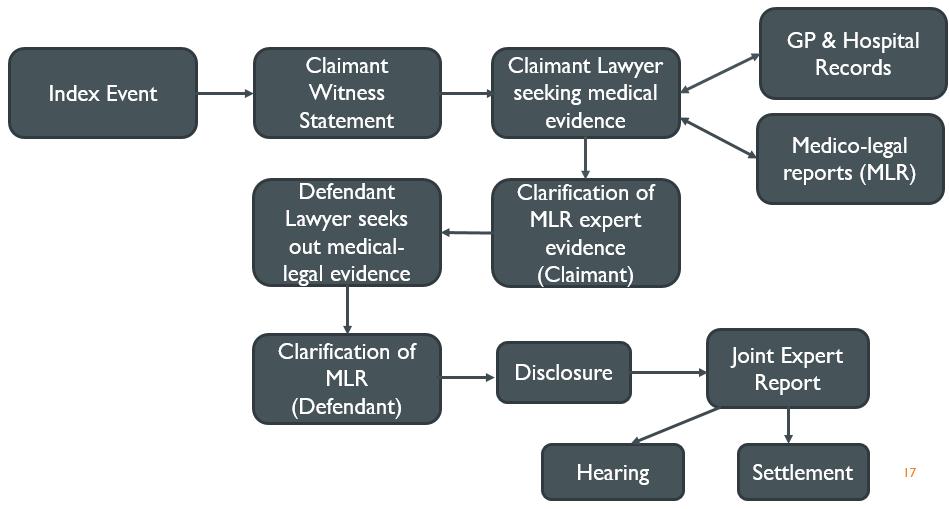

The typical medico-legal trail [6] in progressing a compensation claim is shown below in Figure 1.

The initial assessment by the psychologist expert (instructed by the claimant solicitor) indicated the following information:

Early psychological symptoms were: -

Stress symptoms: Some avoidance phenomena and increased arousal.

Mood Disturbance

Elevated General Anxiety

Social Withdrawal

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy treatment was recommended.

At the second assessment, the expert recommended behavioural‘re-exposure’ practice in a structured and specific way but did not recommend further Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. He acknowledged the specific phobia still existed but was less severe and, in his opinion, should resolve in a further 6 – 12 months.

Clinical aspects addressed by the expert included [7]:

a) Type of diagnosis and range of possible diagnoses. Trauma can result in one of several psychological diagnoses including Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, Adjustment Disorder, Depressive Disorder, Generalised Anxiety Disorder, Specific Phobia. In this case, a specific phobia (travel) was diagnosed.

b) Severity of symptoms and level of disruption. Bearing in mind a ‘default’ model of 3-12 months duration of stress and related symptoms.

c) Need for treatment and motivation to improve. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy was recommended in line with The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines.

d) Likely resolution of residual symptoms. As in (b) above, likely resolution was assessed in line with typical clinical course in trauma symptoms.

These were addressed in line with Koch’s medico-legal postulates [8].

Key clinical aspects included:

• Diagnosis of psychological symptoms: She was diagnosed with a Specific Phobia (Travel) DSM 300.29) (DSMIV 1994; DSMV 2013)

• Duration of symptoms: 30 months and ongoing

• Need for treatment: Initial series of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy sessions then behavioural advice

Medico-legal aspects of case addressed included [9]:

• Pre-existing history of prior road accident three years before

• Other adverse events post-accident (relationship stress; unrelated physical ill health)

• Range of opinion and diagnosis

• Multifactorial causation

• Prognosis and treatment

• Return to work issues

Legal Mind Case and Commentaries undertaken by these authors and their colleagues have identified and illustrated several key medico-legal principles which can be applied to this case [10-13].

a) Onset of trauma following sudden shock [10]: The index event was seen to be ‘shocking’ rather than merely an ‘adverse event’.

b) Material contribution, the ‘but for’ test and plausible and multifactorial causation [11]: causative analysis addressing material contribution and using the ‘but for’ analysis illustrated that the index accident was the material plausible cause of the injuries.

c) Assessing honesty and dishonesty [12]: The expert reached a robust opinion having tested the reliability and consistency of the evidence, and arrived at the conclusion that the claimant was fundamentally honest.

d) Reasonableness and logicality in preparing expert evidence [13]: The expert’s opinion was tested against its own internal consistency and other available evidence to result in the most reasoned and rational opinion.

e) Regulating expert evidence [13]: Throughout the assessment, the expert maintained his impartiality and independence and ‘inoculated’ his opinion by arguing internally using alternative possible opinions.

As a result of bringing this litigation the claimant had two comprehensive psychological assessments by an expert in the field of trauma. She received one series of psychological therapy sessions which alleviated the predominant cluster of psychological symptoms plus advice on resolving her residual symptoms. She also received a financial award to recompense her for her injuries, physical and psychological, and time away from her workplace. Although the process of civil litigation in the UK is fundamentally adversarial, the medico-legal trail involving one expert assessing the claimant twice, allowing for a progressively logical and comprehensive understanding of the genesis, development and resolution of the case of Mrs. C. This combined clinical and medico-legal analysis of one particular case being litigated allows the clinician-researcher to address both clinical and legal aspects of complex personal injury cases and ensure a comprehensive approach to civil case litigation. Further case studies are under consideration addressing different diagnostic and medico-legal features.