The Role of Parents in Cooperative Relationships between Parents and Professionals

It is usual for teams of educational, medical and care-giving personnel to support the educational progress of children who required special needs teaching. Team members can include teachers, special educators, physiotherapists, learning disability nurses, auxiliary nurses and unskilled workers. Professionals are employed in a number of different environments including school systems, respite homes and activity centers. The article describes a working method whereby professionals and parents cooperated in a team around children who required special needs teaching. The primary focus was to increase the understanding of communication, since various functional impairments make mutual comprehension more complicated. Over the course of one-and-a-half years individual video recordings were made of interactions between the child and specific team members in a number of different settings, including school, home and respite centre. The group as a whole came together regularly to view, analyze and reflect on the video data. We discovered, discussed and attempted to resolve the barriers to productive teamwork. In addition, this work was supplemented by in-depth interviews with all participants, and an analysis of the children’s educational records. An important finding was that the project revealed a mutual lack of recognition that parents and professionals have different attachments, experience and knowledge about the pupils’ resources and strategies in communicating with the outside world. Another finding is that the different professions relate to different perspectives and paradigms, which in turn affect what they consider important aspects of how to support the child. The article also identifies experiences with various barriers to progress, and discusses ways of tackling them.

This working method may stimulate ideas for further research into themed work, where the knowledge of close relations may supplement the knowledge of the professionals involved, and contribute to improving the quality of the education provided.

In our experience the availability of DMB in NICU has improved and standardized the use of breast milk and DM for premature babies, using internal protocols and a breastfeeding support practice that has been consolidated over the years.

Keywords: School-Home Cooperation; Multiple Functional Impairment; Video Analysis; Relational Perspective; Special Needs TeachingRESEARCHWhen working with individuals with extensive functional impairments in the context of special needs teaching in schools and kindergartens, reciprocal understandings of attempts at communication between child and professional can present a major challenge. Children with motor, sensory and possibly cognitive functional impairments experience the world differently from children without impairments and they will often express themselves in ways that people around them may find difficult to perceive as meaningful and comprehensible [1]. When the world is sensed and perceived differently, there is also a risk that the person with functional impairments will not comprehend the communication of his or her interaction partner as either a response or as an attempt to initiate contact. Over the course of several decades as a special needs teacher, I found myself in various work situations where I participated in assessing and reporting on complex situations involving young people with functional impairments and those who work with them. My professional practice has focused in particular on working with individuals who have motor, sensory and/or cognitive impairments that are either congenital or were acquired in early infancy. Some young individuals have had a combination of functional impairments in all three areas while others have been affected by either one or two types of functional impairment. In many cases it has been initially uncertain as to the extent to which, for example, cognitive abilities have been affected [1]. As a result, during my practice I have observed many attempts at expressive contact and interpretative response between the child and the other person that have continued as parallel and completely disconnected processes.

For children without recognized functional impariment, the senses of hearing and sight are particularly important for initiating contact and holding attention right from birth. The intensity of this contact is regulared by the manner in which we use our gaze for example, by looking directly at someone and then looking away before resuming eye contact. Gaze is also used to show other people what we are focusing on. We make each other aware of what we are interested in by looking at the person or object that is the focus of our attention. Vocalizing, noises, words and movements accompany actions when we are interacting with others. These are matched in rhythm, intensity and form in dialogical exchanges [2,3]. When all functions are affected by sensory and motor difficulties the combination of impairments will often effectively mask the individual’s perception and cognitive capacity. This makes it a complex and difficult exercise to assess and report on an individual in order to make specific plans for that individual’s educational provision.

Assessments and reports are designed to describe an individual’s problems and to detail resources needed to reduce the effects of their limitations. In my research, I have examined different methods of working with the goal of identifying ways of recognizing each individual’s competences, so that these may to the greatest possible extent form the basis of his or her individualized education plan (IEP), cf. chapter 5 of the Norwegian Education Act [4]. Often medical support is actively involved. It is a matter of course that vision, hearing and other somatic conditions are assessed and then compensated, for instance, by using hearing aids and glasses, and specific conditions are often medicated and sometimes surgery is necessary. Children with severe disabilities often have different health problems, and the medical support system is often heavily involved. In a medical context, the focus is on diagnosing disease, developmental anomalies and pointing to how the condition may or may not be medicated, and compensated in different ways. However, focusing on the benefits resulting from these processes – which can result in substantial improvements in communication and health - can mean that the child’s personal development is given less attention in assessment processes.

Special education as a discipline has a primary responsibility for creating development-support around a child. The primary focus is in looking for the child’s own resources to increase developmental opportunities. I have found that, in the encounter between these two paradigms, mutual misunderstandings can arise. It is true to say that a diagnostic process is a necessary part of developmental work. However, the point is that this process should go hand-in-hand with creative and exploratory educational processes, processes that aim to reveal what resources the individual child possess, and to allow these to have a decisive impact on how plans for the childs’s education is formulated. As a special educator, what I have found is that diagnostic/medical professionals often do not have knowledge or experience of the specific individual’s “story” and background, or their individual competencies and coping strategies. Thus, descriptions made by the experts often tend to resemble general rather than specific descriptions of symptoms and general challenges. In practice, problems arise when general diagnostic descriptions are presented as holistic descriptions of the individual child concerned. Here it is suggested that a person is not synonymous with a diagnosis. In special education this difficulty can be particularly problematic when the designs of IEPs emphasize diagnostic descriptions to the extent that they become decisive influencers for the content and goals of education plans.

In my professional experience, I have encountered many situations where a significant mismatch can be found between a diagnosis of an individual child, and the individual I meet in person. Young people with extensive functional impairments, especially in combination with communication difficulties depend on being represented by someone. Thus they are particularly vulnerable in relation to how this representation takes place. The professional discomfort I have experienced in relation to this mismatch, inspired me to explore different ways of working that pay far more attention to the individual’s existing gifts and talents as a starting point of any remediating process. How might using a different method in the assessment process, which aimed at exploring the individual’s condition, resources and development potential, be helpful? [1].

When working educationally with children with significant educational needs, descriptions of what the child can do and choices of working methods and developmental aims for the individual must be based on in-depth knowledge of the young person concerned. What kind of expressions does this person have/use? What are motivating factors for communication for them? What represents a satisfying quality of life for him/her? Which experiences regarding successful supportive practices have lead to further development? Who possesses the overall knowledge of these practices? - are all key questions guiding this process. In this context, the expertise and experience of the professionals should be considered. However it is those with close relationships and in-depth experience of the individual child’s life have particular knowledge of his/her modes of expression and communication. It is this expertise, most often held by parents/family members that drive the process. Then, the knowledge members of this group hold can be expanded by complementing it with the medical/professional views of others. Ideally this will happen during open and explorative meetings with all interested parties involved in the exchange of experiences and thoughts.

Currently it is questionable as to how much the knowledge and expertise of parents and family members is being taken into account when judgements about developmental progress are being made in Norway. In 2008 the FFOs rettighetsenter1 (The Leagal Advice center) affiliated to the Norwegian Federation of Organizations of Disabled People (FFO) submitted a summary report based on all inquiries they had received during the period from 2005 to 2007, regarding special needs educational practice. These inquiries came mainly from parents regarding the quality of services available to their children, who also recorded that they felt the children’s rights had been ignored by a variety of authorities. Further, parents expressed dissatisfaction with all stages of the educational process, including: the waiting time before expert assessment was conducted by the PPT2, the degree of involvement and inclusion of parents’ views, the lack of information given to them, dissatisfaction with the assessment report and the actual design and organization of the educational plans [5].

The responsibilities of being parents of children with special needs are demanding. Often these include physically challenging tasks and concerns related to health problems and daily –life functions. Parents must deal with a range of disability aids and also communicate their child’s needs to a supportive network. Parents report that they are often the primary driving force in all arenas of their child’s life, despite the rights of the children regarding individualized education plans (IEP) enshrined in the Norwegian Education Act3 , and the right to a more general individual plan (IP)4, supported by the coordinator at the municipal level. This applies to the close care and the work involving organizing the content of the municipal provisions, in schools, kindergartens, respite units and housing.

1http://ffo.no/Rettighetssenteret/

2The Norwegian educational and psychological counselling service

3https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1998-07-17-61

Questions that emerged from my own experiences, together with a summary of the more general situation published in 2008 by the FFOs Rettighetssenter (The leagal Advice Center), inspired me to explore alternative methods of developing a cooperative relationship between medical, psychological, educational institutions and families [5]. I adopted a relational perspective in this project, inspired by the Marte Meo5 method and my knowledge of International Child Development Programme (ICDP)6 as a method of working in groups [6-8]. Marte Meo is a guidance method developed by Maria Aarts in the Netherlands in the early 1990’s. This way of working with videoanalyses is now used in many parts of the world and programs include working with premature babies to elderly people with dementia. The ICDP is a relationship-oriented program based on work in groups of caretakers, developed by Professor Karsten Hundeide and Professor Henning Rye from Oslo University. The ICDP emphasizes promoting the careers and the child’s own resources, and uses various tools and methods to raise carer awareness about the value of meaningful interactions with the child. The goal of the programme is to secure the child’s healthy emotional and mental development. Use of video analysis of interactions is part of this process [9]. My own previous experience of video analysis had been positive, both in clinical settings and in more group-based processes. A video clip is invaluable as a way of capturing the moment for use as an object for a discussion in situations with where communication is unclear, and open to misunderstanding.

I posed the following two general research questions:

• What picture of the conditions under which counselling work is conducted is drawn through the study’s innovative process, in-

depth interviews and analysis of PPT journals?

• What factors seem to be capable of promoting the changes in actual professional practice that the counselling indicates?

In this article, I will in particular present experiences from the first approach. The video counselling project was conducted over one-and-a-half years, and involved a process of sharing and exploring experiences and views, in what ways did we increase our understanding of young people’s way of communicating? What advantages and disadvantages became evident in using video as a tool?

The theoretical tool for the interaction analyses of the videos is taken from what is often referred to as “the new infant paradigm”. This paradigm connects to emerging new knowledge, at the end of the 1970’s, about the infant’s innate competencies. At that time ideas concerning infancy changed in line with the discovery of new knowledge. In particular, film and video had helped to uncover the infant’s active participation in the rhythmic and affective intoned interaction with people in their life-world. During the 1970’s Bateson had studied film footage and discovered what she designated as a proto dialogue, a wordless dialogue early in life with the same structure as verbal dialogue [10]. Later on Trevarten (1999) pointed out the precise dance-like turn-taking, and suggests that this concerns a biological predisposition in humans as a species. Drawing on Colwyn Trevarthen Bråten S further has summarized this development, as did Stern (2010) who is concerned with emotional affective adapting and regulating [11]. All theorists have been major contributors to the emergence of a new paradigm related to the notion of the ‘competent and communicative’ baby. In this view there is a firm conviction that humans communicate from the beginning of life and throughout their lifespan. From the start, babies seek to enter into interactive relations, particularly with people who are relationally close, with an active search for meaning-making processes in their lives. This way of understanding communication competencies in humans at an early developmental level served as the theoretical tool for this analysis. In this view it is not important to discuss whether the expressions of people with functional impairments (hereafter called‘the pupils’) were meaningful, but of great importance to find how we could support each other in finding meaningfulness in expression related to context.

Part of my study included analyzing collaborative processes over the years. To be able to do that I work with adolescents rather than children for this study, as I had access to school journals over a ten years period, and access to Educational-Psychological Service in two municipalities, (in Norwegian PPT)7, to assist with chosing the pupils I was going to focus on. The selection criterion was that I had no previous work experience with the individuals concerned and that the young people had functional impairments of a severe nature - including extensive communication difficulties. The pupils were based in public schools. In the municipalities I worked in there are no private schools, which is very common in Norway. The families can be described as middle-class families, with living and working conditions that reflected this social position.

The research itself was grounded in a qualitative approach, with the objective being to reach an enhanced understanding of the complexities under examination. I had no specific hypothesis to be verified or falsified, but I wished to expand my knowledge about ways of collaborating, and to provide a verifiable set of data that might be of interest to other teaching and medical professionals. The aim was to increase knowledge about the individual resources of all support personnel and to find ways of allowing these resources to guide content and emphasis in the design of developmentally supportive frameworks, including in an IEP.

The fieldwork approach was action research-related. According to Kemmis, there is no clear and unambiguous definition of what action research entails [12]. Typically, the researcher has a high degree of closeness to the field and he/she structures the research agenda with the clear purpose of improving practice. In this regard, Tiller T points to the typical partnership relationship between the researcher and the field, with the goal of developing a better understanding that is then returned from the process and implemented in practice [13]. This accurately describes the agreement of cooperation that was developed between myself and other members of the relational groups. Thirdly, the rationale for working in relational groups with individuals is grounded in an affinity to a phenomenological perspective [14,15]. A phenomenological approach focuses on the individual’s perception of a phenomenon. In this view different people will always perceive the same phenomenon differently [14]. This ontological approach has been criticized for adopting a position with ‘a view from nowhere’ as traditional epistemology presupposes a distinction between the world and the subject [14,16]. However, the objective in the relational groups in this research initiative was not to reach a correct understanding of a real world, but to put our different ways of perceiving and understanding up against each other, utilizing and building on the idea that we did not perceive the phenomena in the same way. Difference and disparity were thus not a threat to agreement and consensus, but an effective and fruitful way to explore opportunities in a process of respectful relational sharing of views and experiences. The work assumes that the target is ?not agreement but the development of a range of angles and tentative interpretations. Finally, I assumed the role of both innovator and researcher, more the facilitator of a process than one that gave good advice and solutions. My theoretical knowledge and experience from the field met the participants’ experiences in a complimentary process, which in no way focused on finding “true” solutions. This aspect of the process was rooted in dialogism, related to Bakhtin’s intriguing distinction between the concepts of dialogue and dialogism [17]. Dialogism is a way of understanding, a process where ideas meet and mutually influence each other. There is little room for the role of the expert in a dialogical process [18].

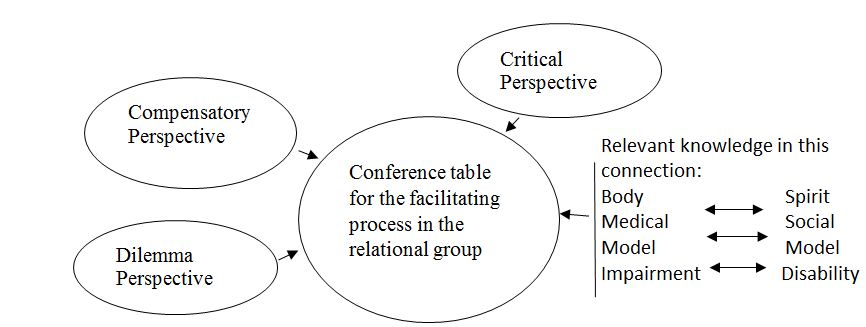

Nilholm C describes how different perspectives shape the view of the one who perceives, and affects what emerges as being the most important [19] (Figure 1). Perspectives are usually not expressed explicitly, and are rarely discussed. According to Nilholm C, the compensatory perspective has a dominant position in special needs education [19]. The perspective is related to the medical model, and focuses on the necessity to rely on expertise in assessment and diagnosis. The aim is to compensate optimally for any disability, so that impacts are minimized in the individual’s meeting with society.

The critical perspective has a greater focus on the societal barriers to disability, and directs a critical look at how society should be changed in order to accommodate human variations. The critical perspective is critical of the compensatory perspective for sorting and separating groups, and maintaining injustice and discrimination.

The dilemma perspective emphasizes that challenges and dilemmas must be understood in their context; they can be addressed and solutions posed, but not finally solved. Time and space implies a dynamic process in the manifestation of dilemmas, which always demand new reflection, new angles to view from and an understanding that solutions are a type of fresh produce that quickly go past their use-by date.

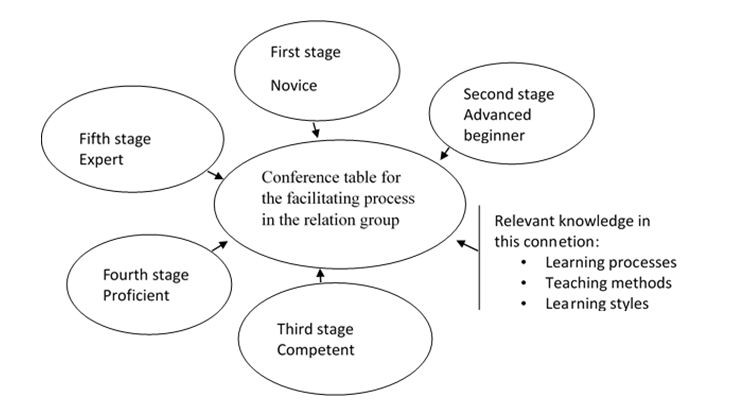

This model is based on a phenomenological approach and focuses on the individual’s acquisition of knowledge and skills, where expertise is the ultimate goal [20] (Figure 2). The immediate response to the above would be that it seems to contradict the idea of group-based skills development in relational groups, where attaining the position of an expert was not a goal. Nevertheless, in our group work, we used descriptions of the strategies people employ in learning processes from novice to reflective and experienced professionals. These descriptions helped us to recognize the questions and comments of those who are inexperienced, and recognize these as a necessary step in professional development. For example, the model describes how the novice focuses on rules and that these are considered a prerequisite for action. The novice lacks understanding of contextual relationships, and the feeling of personal responsibility and commitment is less emphasised. Eventually, the advanced beginner starts to discern patterns, and moves towards more independent interpretation of situations. The competent practitioner has gained so much experience that now the focus is on sorting and grouping experiences. Experiences are arranged in a hierarchy, such as the degree of importance, and there is a greater degree of involvement, responsibility and personal commitment. The proficient practitioner begins to act intuitively and is able to make quick decisions based on a rich supply of experience. His/her actions are responsible, and based on their chosen perspectives and goals. Lastly, the knowledge and skills are embedded in the expert’s personality. His/her actions are fluid and intuitive, and they often struggle to put into words why they act the way they do; choices are associated to experience so that it is almost instinctive [18].

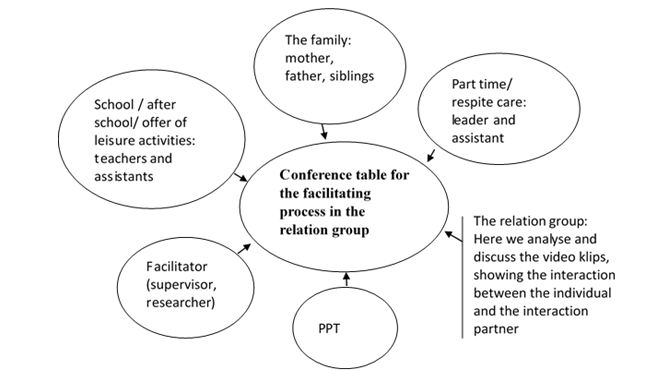

In this section, I briefly explain how participants were chosen for the relational groups, with representatives from close family relations and professionals. Furthermore, a support form for video analysis, which was used in the process, is presented. Another important focus area was the work of recognizing and acknowledging how different perspectives form our understanding, and how different experience and expertise in the field affects how we participate in the discussions. In cooperation with the parents, typical 24-hour day charts were drawn of the pupils’ daily lives. These 24-hour charts were very individual, and showed the various respite measures, time at school, after-school programs and any other support and activities available for the pupil. When the weekends were included in the chart, a clear picture emerged of where the pupils spent most of their time. In cooperation with the parents, who were often the only ones with a good overview of everything that was available to the pupils, it was discussed and decided who were the significant caregivers in the pupils’ lives.

Example: pupil with 50% respite support:

An overview of the pupil’s routine for a single day in week 1:

• 8 am – 2 pm - school (daytime – Monday to Friday)

• 2 pm – 3.30 pm – after school program (daytime Monday to Friday)

• 3.30 pm – 8 am the next day – at home (afternoon/evening + night-time, Monday to Friday)

• Leisure activities: 1 to 2 hours per week

• Weekend: two days with parents

Week 2 could look like this:

• 8 am – 2 pm - school (daytime – Monday to Friday)

• 2 pm – 3.30 pm – after school program (daytime Monday to Friday)

• 3.30 pm – 8 am the next day – respite care unit (afternoon/evening + night-time, Monday to Friday)

• Leisure activities: 1 to 2 hours per week

• Weekend: Two days in the respite care unit

An overview of who the pupil spends the most time with on a daily basis:

• Home: mother, father, siblings, grandparents?

• In school: teacher, special needs teacher, assistant?

• In the after school program: assistant?

• In the leisure activities: assistant?

• In the respite care unit: professional, assistant?

This was mapped visually as a 24-hour day, and gave a concrete illustration of how the pupil spent most of their time. This provided a basis for discussion of who had the most interaction experience with the pupil, and opened up a more informed understanding of who knew the pupil best and had significant experience and knowledge of the pupil. The relational groups were composed on the basis of this discussion, and PPT was invited to participate in the video counselling process.

Three different approaches were used to structure the research project as a case study. These are as follows:

1. I invited people involved in networks around two young people with multiple functional impairments to participate in a video counselling project running over the course of three semesters, or one-and-a-half years. In dialogue with the young people’s families a relational group around each individual, in which significant interaction partners in the individuals’ lives participated, as established. Our task became to explore, using video as a working tool, how we might increased a shared mutual understanding about the young person in order to promote meaningful communication.

In total, 25 field visits were completed. I kept detailed field notes of the process.

2. After three semesters, I conducted qualitative in-depth interviews with all participants during the following year. I wanted to find out what experiences could be drawn from this manner of cooperation. Could one develop a method that could inspire others in similar situations? Was this a way of working that could eliminate some of the difficulties identified in the research conducted by the FFO’s Legal Advice Centre?

Nineteen informants were interviewed for a total of slightly over 25 hours.

3. An analysis of the young persons’ PPT records was planned as part of my research, in an attempt to find out what counselling and assessment processes had taken place previously. What knowledge was expressed in the many reports, statements, applications and individualized educational plans (IEPs)? Who had contributed their experience and knowledge, and how had cooperation between the families and the system around them been organized?

I analysed a total of 1,067 pages [1].

The meeting of different experiences and the relationships to the pupil captured the flow of knowledge in the network (

Figure 3).

I spent time in all these places, half to one hour in each setting before an everyday activity between the pupil and interaction partner was chosen. This encounter was then videotaped. Between the visits, meetings were carried out in the relational groups. In preparation I analysed the video clips in advance of the relational group meetings, where I used a support-form for the video clip analysis, which was developed in an earlier project associated with “Småbørnstilbudet” in Copenhagen [22]. I wrote field notes immediately after each visit.

Illustration 2: Support-form for the video analysis [23]

At the meetings, those that had participated in the video clip were asked to talk about their own experience of the situation (Table 1. It was agreed that we would not use any video clips for analysis unless the participant was present at the meeting.

The groups consisted of professionals with different educational backgrounds and experience. Some had an educational or special needs teaching background, while others had educational backgrounds that lay at the intersection of health and education, while yet others were professionals from the fields of health and medicine. Many had little education in the field and worked in assistant positions. There were 14 professional participants in the relational groups, nine of whom were educated as assistants or unskilled. Several aspects of the group work were highlighted in the analysis of field notes. Briefly, two aspects that affect the quality of a group process will be highlighted here: different perspectives and extent of experience.

Based on findings in the project’s pilot part, the work was organized so that I could go on separate field visits to all the arenas where the pupil was [1]. The importance of this may be explained by the fact that we tested two different working methods in the pilot project [1]. In one of the video counselling processes, I had video footage sent to me without having been present during the video-filming process; in the second process, I did the video filming myself. This exercise convinced me that my presence during the video filming was absolutely necessary because information about the context was not always evident in the video clip. Further, presence during the process gives you access to intuitive experiences, tensions in the room, events preceding the filming, body tensions and breathing rhythms: all what we perceive as stress or calm but which is poorly shown on a video clip. The interaction partner on the video clip had the most intimate experience of how contact was experienced. The same principles have been applied in the work outlined in the use of video analysis in teams [18].

In the evaluation of the pilot project, the pilot group pointed out that the leader of the video analysis process should have expertise in three key areas, as below [1]:

1. High professional expertise in the field.

2. Leadership skills, involving the ability to plan, organize and allocate tasks.

3. Relational competence, which concerns being able to ensure the group’s open pursuit of complementary ways of understanding, and preventing developments that head towards static definitions of what is right and wrong, and negative personal characterizations.

The work in the relational groups went well, with active participation in sharing views and experiences. I noted with interest that there were not large differences between the contributions of the close relations and those of the professionals. The sharing of views and the search for alternative ways of understanding seemed similar. Each relational meeting was evaluated, and I attempted to find out the positive and critical aspects of the way we worked to try to get behind this seemingly positive consensus. Before the fifth meeting of the relational groups, I edited all the video clips into a single video film and related the essence of the new thoughts and ideas the process had given the group to the combined video.

I then asked for a fundamental evaluation if this represented new knowledge for everyone.

Moreover, if we consider the cost of the care of premature babies with clinical or surgical NEC, the savings are quite extensive.

This meeting was a key turning point in the process. The groups separated into two quite clear camps. The parents expressed that most of the conclusions the group had arrived at concerning the children’s competencies confirmed what they already knew. Nevertheless, there were many aspects of the discussions that contributed to new ideas. It had been a positive process to participate, and to highlight the children’s competencies that everyone in the group agreed on.

The group of professionals expressed that they had gained new knowledge and increased their knowledge of the pupils’ competencies, and that the process had given them many new angles to adapted facilitation. However, discussion emerged between the parents and the professionals at which time they questioned each other’s standpoint positions. One mother expressed disappointment that it seemed that the professionals were not initially aware of the pupil’s competencies. A father said he almost felt guilty that he had not previously communicated to them his knowledge of his child well enough. Thus, a dialogical process came to support the discussions, and we focused on how we could cooperate in the future to knowingly complement each other’s knowledge as we found that we had had notions about each other’s knowledge which had proved to be incorrect. The conclusion was to continue working in relational groups after concluding the project, where one could apply what had been learned and experienced as a parent and as a professional. Concretely, the group work showed how tacit knowledge must be put into words. Professionals should ask and inquire which is a prerequisite for parents to have the confidence and courage to communicate their knowledge [1].

The work in the relational groups was mainly grounded in a dilemma perspective, but in the discussions differences of opinion arose that were clearly based on different perspectives. However, because the groups had discussed this point it became possible to recognize and understand disagreements on another level. One example of this - and a group “aha” moment - was a discussion between an educator and a health care professional. The episode concerned a pupil who needed assistance to eat. The educator focused on interacting with the pupil to encourage him to become more involved in his own mealtime. Thus, the educator focused on how to “read” the pupil’s behavior signaling the “time for a new spoon of food”, or “now you had to wait”, and so on. The health care professional was more focused on the pupil’s nutritional needs, and expressed that the pace of eating adopted by the educator was too slow. This professional wanted to find another way to support the pupil during mealtime. However both of them managed to meet the other with a sense of wonder about the other’s justification and understanding. Both became aware that while the one focused on communication, the other professional had focused on the pupil’s nutritional needs. The ensuing discussion of how these two foci were related exemplified a typical example of a dialogical process. Could it be that the pupil would eat more if he were able to participate and take more control of his own mealtime? Could the educator take into account that the nutritional situation also must be taken into consideration? Thus, a further development of the mealtime would have to draw on ideas facilitated by both perspectives.

The relational groups consisted of professionals with different amount of experience from the field. This too is something that is rarely discussed as a factor affecting the content of professional discussions. The observations, documented in the field notes, showed that there were small, almost invisible alliances in the group in the discussions. The way this arose could be when a question associated with a video analysis was raised, and you could see that someone exchanged glances and said that they had had much experience with that type of behaviour when an individual acted in such a way, and that it usually had a specific reason. This was an effective way of using their experience to make more inexperienced group members quiet and passive, i.e. nobody wants to come across as being uninformed. However, becoming aware of this phenomenon also made it possible to talk about it. In particular, facilitators should not make this mistake and confirm with a nod, support or the like to those who are at the same level of experience as themselves. If groups work in this way there is a great risk that the field will not develop professionally, when the inexperienced are excluded and not included in the field. For discussion of this phenomenon, Dreyfus and Dreyfus may be used as a theoretical tool to focus on the different strategies people use when they acquire new understanding and skills [20].

When a group acquires knowledge and understanding of how the strategies of different group members are related to a learning process, depending on the individual’s experience, it becomes harder to ignore them or make overbearing comments. In this context, phenomena such as blind knowledge were discussed - where the individual stops being curious after reaching a static understanding that they are ‘fully trained’ [21]. There was a gradual realization that a group needs variations in knowledge levels and the presence of the inexperienced individual who asks open and so-called naive questions which some of the others, themselves, may have stopped asking.

Through using video as a working tool in relational groups around pupils for a period of one-and-a-half-years I had a unique opportunity to conduct research into a working method that provides concrete support for section 1-1, first paragraph of the Education Act, which states that there shall be cooperation between the school and the home. Section 13 of the Act also deals with cooperation with parents, with sub-section 13-3d providing:

The municipality and the county council shall endeavour to cooperate with parents both in primary and lower secondary school and in upper secondary school respectively. The organization of cooperation with parents shall take account of local circumstances. The ministry will enact more detailed regulations (Education Act, 2016).

It was particularly significant to experience how professionals and parents could encounter each other in processes with mutual exchanges of knowledge and experience. This exchange in dialogistic processes is certainly not without its challenges. In particular, the fifth meeting’s evaluation probed the parents’ and the professionals’ perceptions of each other, revealing a need for openness and sharing about the resources that the young people were actually thought to possess. The group of professionals gained insight into the fact that parents possessed a bank of knowledge about their children, and that this knowledge – when it is supplemented with the professionals’ specialist knowledge – could be a force for assuring the quality of the educational provision. In the same way, parents came to understand that what might be referred to as their latent knowledge must not be taken for granted or as knowledge that the professionals were also aware of. Having confidence that this is important knowledge requires openness at a systematic level in schools and municipalities, where the parents’ knowledge should be systematically sought, perhaps particularly when an IEP is to be developed. Such systematic attempts to seek the parents’ knowledge are not adequately embedded in current case-management procedures. This was established in a report from the FFO’s Legal Advice Centre (Rettighetssenteret, 2008). The report also revealed how a group process must focus on how it is important to work directly with different perspectives and levels of knowledge in order to create an open search for the power inherent in different understandings, and recognition that being different is an opportunity, not a problem.

The following year of the research initiative, during which levels two and three were implemented, involved interviews with all the participants and the analysis of the young people’s records. At this time another aspect of this way of organizing cooperation was revealed. Despite the informants’ very positive feedback about the process, the groups had not managed to maintain activity as they had planned after the end of the project period. The work method had been based on relational groups around the pupils, and the project had been allocated adequate resources for one-and-a-half years, but had not gained sufficient support among the school management team or at a political level. Continuing the work independently required resources for substitute staff and for preparation time for the relational group leader, and these resources had not been provided. The weakness of the project was that it was not embedded within a visionary plan for schools or the municipality. The experience we gained was in no way lost or worthless, as the quality of educational provision to the pupils in question was improved. The problem going forward is that the experience will not be implemented into practice at a systematic level.

This method of working may be recommended to professional practitioners, as it is exciting and creative. Experience supports the pilot project’s finding that this type of work makes demands on professional competence, managerial competence and relational competence. In addition, I wish to point out that this type of project must obtain the support of the school’s management team, municipal managers, and politicians. There are many reasons why this may seem complicated. As a starting point, there are the same formal requirements for teaching competence for special needs teaching in primary and lower secondary school and upper secondary school as for the teaching of the standard curriculum. In addition to the formal competence requirements, the school owner is responsible for ensuring that special needs education contributes to ensuring that the pupil gains a reasonable benefit from the teaching provision. The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training’s guidance on special needs education provides that schools may not use teaching assistants as teachers [24]. If a teaching assistant is to be used, this must be expressly stated as the pupil’s individual decision. There must be a specific evaluation to establish whether the use of an assistant, and the extent to which the assistant will be used, are justifiable and adequate for education to be provided to the child or young person. In our project, the use of unskilled teachers was the rule, and not the exception. An article by the deputy leader of the Union of Education Norway (Utdanningsforbundet) discusses the problems posed by the 70% rise over a three-year period in the proportion of teaching assistants employed in special needs teaching in Norway [25]. This confirms that our experiences in a local project are symptomatic of a general problem.

The use of untrained assistants in special needs teaching entails a risk that professional needs will not be disseminated upwards into the system. Another situation that our project revealed was that the use of untrained assistants resulted in fast turnover and instability among staff members, since untrained assistants were seldom employed on a permanent basis. The analysis of the pupils’ PPT records revealed a link between the competence of the suppliers of their educational provision and the implementation of provisional goals in processes with specialist assessments and reports. Detailed specialist educational measures make demands on professional competence when a plan is to be implemented in real life, and this competence was often absent.

The pupils in our project were a very vulnerable group with extensive functional impairments and communication difficulties: they comprise a group that is often described as people with developmental impairments. The Research Council of Norway has recently published a report on special needs teacher education and research, with a focus on future requirements. The report contains a review of future competence requirements, and in this context indicates a clear unmet need for special needs teachers to work with people with developmental impairments [26]. Accordingly, an improvement in the quality of the special needs teaching offered to the young people in our project would require prioritization on many levels: in the specific school, municipality and county council, and in the design of special needs teacher education programmes in Norwegian higher education institutions. There is a need for more research in this field, not least for research into how one may increase the quality of special needs education in accordance with the rights set forth in the Education Act. Requirements concerning professional competence must be complied with, and professional development in this field must be prioritized.