Topical Fenticonazole Exposure in Pregnant Women: Risks for the Pregnancy and Foetus? A Comparative Study in the EFEMERIS Database

Objective: The aim of this study was to assess pregnancy and foetal-related risks following exposure to topical fenticonazole in pregnant women (natural pregnancy termination, preterm birth and major congenital anomaly).

Study Design: A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data of women enrolled in the French EFEMERIS database between 2004 and 2018. The study compared natural pregnancy termination (including miscarriages and stillbirths), major congenital anomalies and preterm birth between pregnancies exposed to fenticonazole and pregnancies not exposed to azole drugs through multivariate analyses.

Results:Among the 7,209 fenticonazole-exposed pregnancies, 1.4% resulted in natural pregnancy termination. The rate of premature birth in exposed new-born infants was 5.2%. Among the 2,082 foetuses/new-born infants exposed to fenticona- zole in the first trimester of pregnancy, 2.5% developed major congenital anomalies.

Results: The Sample Had Patients’ Gender as Follows: There Were 29 Male Individuals (46%) And34 Female Individuals (54%) Hence The Sample Was Relatively Dominated By The Female. The Sample Of The Study Had Mean ANB Angle Of 2.3, And The Standard Deviation Was 3.4. Whereas The Age Mean Was 16.9 With A Standard Deviation of 3.8. That Define That the Sample (N= 63) Had Individual Age Ranging From 12 Years (Minimum) Which A Documented Mean Value of 16.97 In Age Category with Standard Deviation of 3.8. Conversely ANB (Mean Values 2.3) Levels Were -7.6 At Minimum and 7.2 Maximum with Standard Deviation of 3.4.

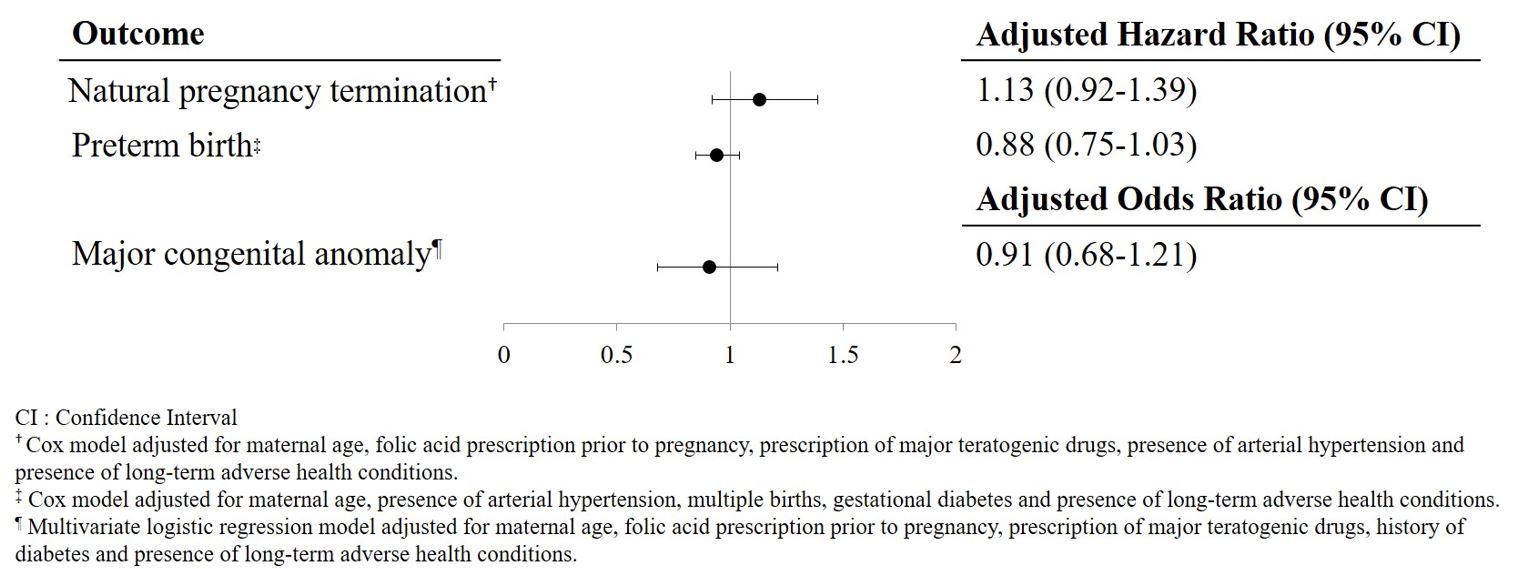

Multivariate analysis did not highlight an increased risk of natural pregnancy termination in pregnancies exposed to fen- ticonazole (HRa=1.13 [0.92-1.39]) or a risk of preterm birth (HRa=0.88 [0.75-1.03]). Similarly, we did not identify an in- creased risk of major congenital anomalies in foetuses exposed to fenticonazole in the first trimester of pregnancy compared to unexposed foetuses (ORa=0.91 [0.68-1.21]).

Conclusion:This study does not identify any increased risk of termination of pregnancy, prematurity or malformation in women exposed to topical fenticonazole during pregnancy compared to a control cohort not exposed to azole-based drugs.

Keywords:Pharmaco-Epidemiology; Fenticonazole; Pregnancy; Congenital Anomalies; Pregnancy Termination; Preterm Birth

Several studies suggest that pregnant women are more vulnerable to certain infections, mainly vaginal infections [1,2], as a result of physiological and immunologic adaptations [3]. Vaginal candidiasis is the most common gynecological infection during preg- nancy. According to recent studies, up to 40% of women have vaginal colonization with Candida during pregnancy [4]. These infections during pregnancy could be associated with an increased risk of maternal and foetal complications such as miscarriage, preterm birth and low birth weight [5,6].

Paradoxically little is known about the risks of antifungal treatment on the course of pregnancy or on the foetus [7]. Mucocutane- ous fungal infections can be treated with various antifungal medications including azole antifungal agents. These agents, used topi- cally, are usually sufficient to treat vulvovaginitis or cutaneous fungal infections during pregnancy. All topical azoles are effective, but clotrimazole [8,9] and miconazole [8,10] are preferred due to more reinsuring data in the medical literature about their use during pregnancy. There are few data on the risks of other azoles in pregnant women. Apart from azoles, nystatin and amphotericin B are another possible topical treatments. There is no evidence of embryotoxic or fetotoxic effects secondary to nystatin but vaginal nystatin may not be as effective as azoles [11]. There are few reports of use of amphotericin B in pregnancy for treatment of leishma- niasis without adverse fetal effects [12]. Oral azole treatment is only indicated in severe primary infections or infections resistant to topical treatment. In this case, fluconazole or itraconazole could be used in pregnant women. There has been no increased risk for miscarriage, stillbirth, congenital malformation, prematurity or low birth weight in studies when fluconazole is used at low doses [13]. Birth defects (cranium, face, bones, heart) were reported after first-trimester maternal intake of high doses for a longer time [14]. So, fluconazole should be used with special caution during the first trimester of pregnancy. Studies on itraconazole include few women but did not find an increased teratogenic risk [15].

In France, the most commonly used topical antifungals in pregnant women are econazole, sertaconazole and fenticonazole. Fenti- conazole is used by 5% of the French pregnant women [16] while there is no human data on the risks during pregnancy.

Fenticonazole is an imidazole with a broad spectrum of antimycotic and antimicrobial activity and appears to be at least as effective as other topical antifungals in the treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis and can also have a major role in the treatment of mixed vaginal infections of the genital tract [17]. Pre-clinical studies have not highlighted any teratogenic effects in animals [18], but embryotoxic and fetotoxic effects have been observed following the administration of very high oral doses. However, in France, fenticonazole is only marketed for topical use (vaginal suppository and cream) [19].

To address the lack of data about fenticonazole and pregnancy, we studied potential pregnancy and foetal risks after exposure to topical fenticonazole with specific focus on the risks of natural pregnancy termination, preterm birth and major congenital anomaly.This objective was met by conducting a retrospective cohort (“exposed-unexposed”) study using data from the French EFEMERIS [Evaluation chez la Femme Enceinte des MEdicaments et de leurs RISques (Evaluation of medicines and their risks in pregnant women)] database [20]. The study compared natural pregnancy termination, major congenital anomalies and preterm birth be- tween pregnancies exposed to fenticonazole and pregnancies devoid of azole exposure.

EFEMERIS is a French database including pregnant women in the general population. It was developed to study risks associated with drug exposure during pregnancy. At the time of this study, the database listed more than 144,200 pregnancies in the Haute- Garonne region, a department of South-West France.

The data were collected from several partners. Firstly, the French Health Insurance System (Caisse Primaire d’Assurance Maladie; CPAM) of Haute-Garonne records all the reimbursed medicines [names; ATC code (Anatomical, Therapeutic and Chemical clas- sification system) and dispensing dates] prescribed and dispensed to patients with general state insurance cover (approximately 86% of the Haute-Garonne population). CPAM also provides data on pregnancy terminations (dates without specific medical information). Secondly, data were collected from Toulouse University Hospital (CHU Toulouse); the Prenatal Diagnosis Centre (Centre Pluridisciplinaire de Diagnostic Prénatal; CPDPN) provides data on congenital anomalies in pregnancies for which thera- peutic abortion has been considered (cause and date of termination); the Hospital Medical Information System (Programme de médicalisation des systèmes d’information; PMSI) provides data on pregnancy terminations performed in the CHU Toulouse [type (induced abortion, stillbirth and miscarriage) and date of termination]. Thirdly, the French National Mother and Child Welfare Service (Protection Maternelle et Infantile; PMI) records health certificate data from the medical examinations conducted at birth and at 9 and 24 months. The health certificates are completed by a paediatrician or general practitioner, using a standardised questionnaire. They contain data about the mother (age, level of education, etc.) and the child (gender, prematurity and congenital anomalies).

Each year, the CPAM selects data about pregnancies of the last year; pregnancies for which outcome is available are included in EFEMERIS database. Consequently, pregnancies for which data about medicines or outcomes is not available, or for which women refused to participate to the study (less than 80 women per year), are not included in the study. Every year, data concerning around 9,000 women-outcome pairs is added to the database.

Approval for setting-up the EFEMERIS was granted by the French Data Protection Agency on 7 April 2005 (authorisation num- ber: 05-1140). Women were informed of the study and could refuse to participate.

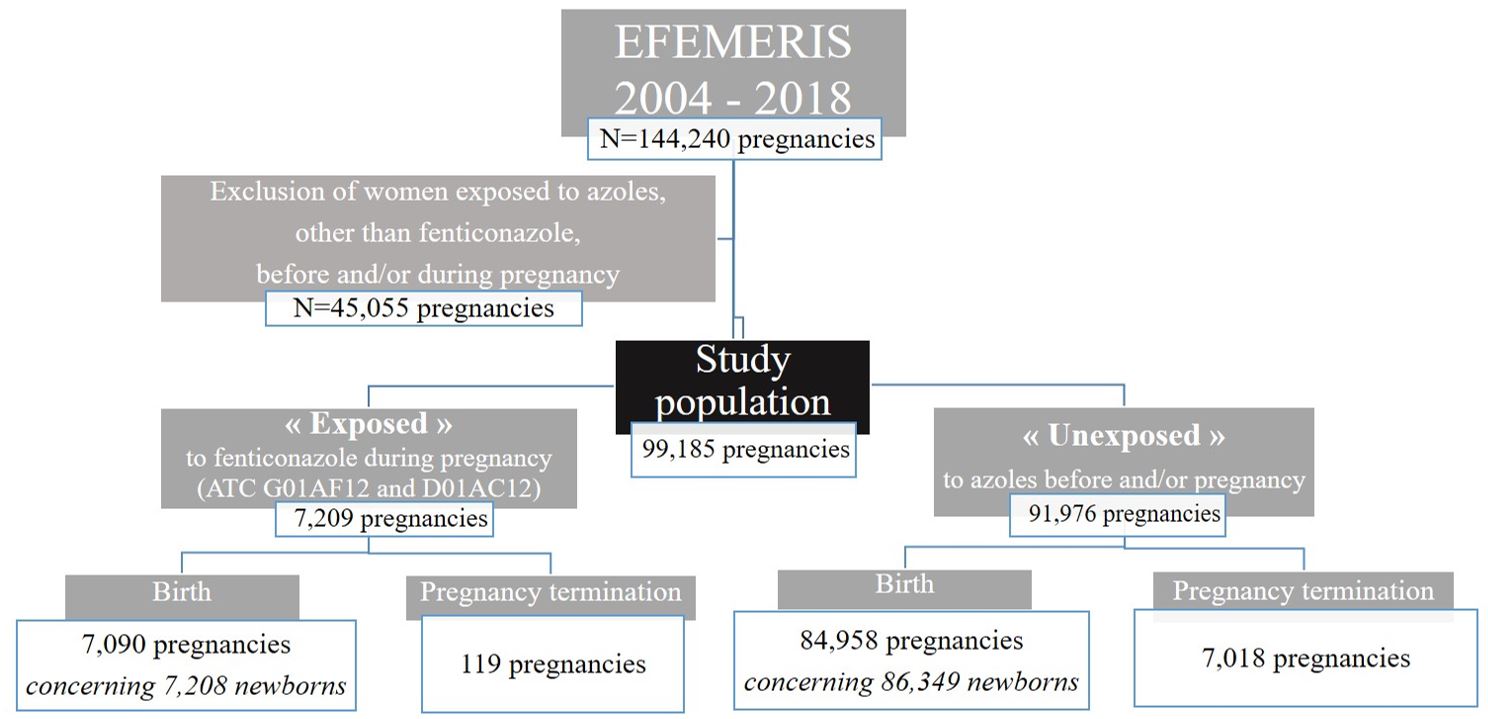

Women included in the EFEMERIS database who had a pregnancy outcome between 1 July 2004 and 31 December 2018 were enrolled in this study. However, women not exposed to fenticonazole but exposed to other azole drugs before and/or during preg- nancy were excluded. The pregnancy start date (conception) and end date are available for each pregnancy. If a woman had more than one pregnancy during study period, she was reconsidered more than once.

Pregnant women were classified according to their exposure status to fenticonazole during pregnancy (exposed or unexposed).

In France, fenticonazole is only available in topical pharmaceutical form (vaginal suppository and cream). The database does not contain data about dose and duration. However, in France, in case of vaginal infection, health authorities indicate fenticonazole vaginal suppository with a dosage of 600mg (in 1 administration of 600mg or 3 administrations of 200mg).

A woman was deemed “exposed” to fenticonazole if this drug was dispensed at least once during her pregnancy (ATC code “G01AF12 – Genitourinary system and sex hormones” and “D01AC12 – Dermatologicals”). A woman was classified in the “un- exposed group” if she did not receive azole drugs three months before and/or during pregnancy.

Exposure per trimester of pregnancy was defined as follows: exposure during the first trimester of pregnancy if the drug was dispensed between conception and the 15th week of amenorrhoea (WA), during the second trimester between 16 and 27 WA and during the third trimester between 28 WA and delivery.

When investigating major congenital anomalies, exposure to fenticonazole during the first trimester (the period of organ develop- ment and thus of maximum teratogenic risk) was considered. With regard to prematurity, only pregnancies exposed to fenticona- zole between 22 and 37 WA - the prematurity risk period - were considered in the analyses. Exposure to fenticonazole throughout the entire pregnancy was considered for natural pregnancy terminations.

Several maternal characteristics are described in this manuscript. These include maternal age, long-term adverse health condi- tions (Yes/No), multiple births, gestational diabetes, pre-gestational and/or first-trimester diabetes, arterial hypertension during pregnancy, folic acid dispensed prior to pregnancy and the dispensing of major teratogenic drugs (valproate, oral anticoagulants, antimitotics, mycophenolate, oral retinoids and thalidomide).

In EFEMERIS database, we do not have the indication of the drugs and only have the pathologies requiring hospitalization or specified on the health newborn certificates. Therefore, we developed algorithms to create some variables; “Gestational diabetes” was defined as prescriptions of antidiabetic medicines during the 2nd and/or 3rd trimester(s) and not before. “Pre-gestational and/ or first-trimester diabetes” was defined as prescriptions of antidiabetic medications in the 3 months prior to conception and/or in the first trimester of pregnancy. “Arterial hypertension” during pregnancy was defined as more than 2 prescriptions of antihyper- tensive medications before or during pregnancy, and/or the presence of arterial hypertension during hospitalisation (PMSI), and/ or information mentioned in the health certificate on day 8 (PMI), and/or in the CPDPN file.

Adjustments for confounding variables were made during the multivariate analyses. Confounders were selected using scientific literature and univariate analyses to assess the link between potential confounders and outcomes. However, only potential con- founders with less than 5% of missing data were taken into consideration and included in the multivariate analyses.

Standard descriptive statistics were used by presenting continuous variables as the mean [± standard deviation (SD) and the range] and categorical variables as the number of patients and percentage. The characteristics of the pregnant women and data on the foetuses/new-born infants were described. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables between groups, and Student t-tests to compare quantitative variables.

Multivariate analyses were used to study associations between exposure to fenticonazole during pregnancy and outcomes.

For pregnancy termination and prematurity, Cox proportional risk models estimating Hazard Ratios and their 95% Confidence Intervals (HR - 95% CI) [21,22] were applied in order to take into account the time-dependent variable of exposure to fenticona- zole. Thus, a woman was assigned to the “exposed” group from the date of the first prescription of fenticonazole during pregnancy until the end of the pregnancy, and to the “unexposed” group prior to the first prescription or when no prescription was given. As previously mentioned, in terms of prematurity, only fenticonazole prescriptions between 22 and 37 WA were considered. Gesta- tional days were used as the underlying period.

Otherwise, logistic regression models were used to analyse the potential effects of fenticonazole exposure on the rate of major congenital anomalies by calculating the Odds Ratios (ORs - 95% CI). Only foetuses/new-born infants exposed to fenticonazole in first trimester of pregnancy and cases with information on the presence or absence of congenital anomalies were included in this analysis (live births, stillbirths and medical terminations of pregnancy). A sensitivity analysis including exposure during the specific period of organogenesis (from 2 to 10 WA) was also performed.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS® version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A bilateral significance level of 5% was applied for all statistical analyses.

Our study involves 99,185 pregnant women including 7,209 “exposed” at least once to fenticonazole during pregnancy and 91,976 “unexposed” to azole drugs before and/or during pregnancy (Figure 1).

Overall, 7,209 pregnant women were prescribed and dispensed fenticonazole during pregnancy, corresponding to a prevalence of 5.0% (basing calculations on the entire EFEMERIS population, N=144,240).

Among these 7,209 women, 2,600 (36.1%) were prescribed fenticonazole during pregnancy only as a vaginal suppository, 1,090 (15.1%) received only cream and 3,519 (48.8%) were prescribed both pharmaceutical formulations (vaginal suppository and cream). In addition, 3,414 pregnant women (47.4%) received both pharmaceutical formulations of fenticonazole on the same prescription.

Among women exposed to fenticonazole, 29.6% received fenticonazole during the 1st trimester of pregnancy (n=2,132), 44.0% during the 2nd trimester (n=3,134) and 40.5% during the 3rd trimester (n=2,871). Only 1.0% received fenticonazole in all three pregnancy trimesters (N=69).

The average number of fenticonazole prescriptions during pregnancy per exposed woman was 1.3 (±0.6 [minimum=1, maxi- mum=11]). Almost 81% of pregnancies had single prescriptions of fenticonazole during pregnancy.

As shown in Table 1, there were fewer exposed vs. unexposed employed pregnant women. Gestational diabetes was more prevalent in those who had exposure with fenticonazole compared to unexposed women. Pregnancies exposed to fenticonazole were pre- scribed and dispensed more medications, on average, during pregnancy than unexposed pregnancies. Exposed pregnant women were prescribed more antibiotics than unexposed pregnant women.

Women who received fenticonazole in all three trimesters of pregnancy (N=69) appear to suffer more co-morbidities (1.5% of pre- gestational and/or first-trimester diabetes, 8.8% of long-term adverse health conditions for example) and to be less active (40.9% of employed pregnant women).

Pregnancy outcomes in the 2 groups are described in Table 2 and discussed in detail below

Among the 7,209 fenticonazole-exposed pregnancies, 119 (1.7%) resulted in pregnancy termination (including 1.3% of termina- tions before 22 WA, 0.2% at 22 WA or after, and 0.2% of terminations for medical reasons) compared to 7,018 (7.6%) of unexposed pregnancies (including 6.7% of terminations before 22 WA, 0.2% at 22 WA or after, and 0.7% of terminations for medical reasons). When only natural pregnancy terminations (miscarriages and stillbirths) were considered, 1.4% of pregnancies were prematurely interrupted in the exposed group and 6.3% in the unexposed group.

Among the foetuses/new-born infants exposed to fenticonazole in the first trimester of pregnancy (N=2,082), 2.5% developed major congenital anomalies compared to 2.6% in the case of foetuses/new-born infants not exposed to azole drugs.

The premature birth rate in exposed new-born infants was 5.6% compared to 6.5% in the unexposed group. Of the premature neonates exposed in utero to fenticonazole, 87.1% were born between 32 and 37 WA (moderate to late preterm), 9.4% between 28 and 31 WA (very preterm) and 3.4% were born before 28 WA (extremely preterm). Prematurity levels in neonates not exposed to fenticonazole in utero are close to the distribution pattern in the exposed group (87.2% moderate to late preterm, 9.8% very preterm and 3.0% extremely preterm).

Figure 2 highlights the results of the multivariate analyses concerning the 3 pregnancy outcomes studied: natural pregnancy ter- minations, major congenital anomalies and preterm birth.

Multivariate analysis did not show an increased risk of natural pregnancy termination in pregnancies exposed to fenticonazole after adjusting for maternal age, folic acid prescription prior to pregnancy, major teratogenic drugs, presence of arterial hyperten- sion and long-term adverse health conditions.

Likewise, multivariate analysis did not reveal an increased risk of major congenital anomalies in foetuses/new-born infants ex- posed to fenticonazole in the first trimester of pregnancy compared to unexposed foetuses/new-born infants after adjusting for maternal age, folic acid prescription, major teratogenic drugs dispensed, pre-gestational and/or first-trimester diabetes and long- term adverse health conditions. Using sensitivity analysis, no association was found between major congenital anomalies and exposure to fenticonazole only during organogenesis (ORa=0.87 [0.59-1.28]).

Finally, we did not witness an increased risk of preterm birth (following exposure to fenticonazole in utero, after adjusting for maternal age, presence of arterial hypertension, multiple births, gestational diabetes and presence of long-term adverse health conditions.

Pregnancies exposed to both form of fenticonazole (vaginal suppository and cream), probably with severe infections, do not ap- pear either to be more at risk of natural pregnancy termination, major congenital anomalies and preterm birth.

This study did not highlight any increased risk of pregnancy termination, prematurity and malformation in women exposed to topical fenticonazole during pregnancy compared to a control population of women devoid of azole exposure.

In our study, the women exposed to fenticonazole had a lower level of education, were more often unemployed and used more medicinal products. Similarly, several published studies show that mycoses are more common in individuals with poorer living conditions [23] (poor hygiene, poverty, etc.) and presenting chronic conditions such as diabetes [24, 25]. The use of antibiotics is also a known factor in the onset of fungal infections. The women in our study who were prescribed fenticonazole also used more antibiotics than women not exposed to azole-based medication.

The data analysis does not highlight an increased risk of malformation in women exposed to topical fenticonazole during preg- nancy. This result corroborates the findings of animal studies which did not reveal any teratogenic effect in rats and rabbits [18].

No studies on the risks of this drug in pregnant women were found in the medical literature. Among other topical azoles, clotri- mazole, miconazole and nystatine were the most evaluated in pregnant women. An Israeli study including 1.993 women exposed to clotrimazole and 313 to miconazole did not find an increased risk for major malformations following first-trimester exposure to vaginal form [8]. There is no evidence of embryotoxic or fetotoxic effects secondary to nystatin [26] but vaginal nystatin may not be as effective as azoles [11]. In France, nystatin vaginal tablets is no longer available in the pharmaceutical market. We located less publications about sertaconazole and econazole. A study in EFEMERIS comparing 16,222 women (15.0%) who were given sertaconazole during pregnancy and 91,976 who were not exposed did not show an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome and major congenital anomalies from exposure to topical sertaconazole [16]. For econazole, there are limited human reports, but no increase of the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome was reported [27]. For all other topical antifungals, no or little human data have been published.

According to pharmacokinetic studies, the systemic uptake of fenticonazole following cutaneous application is of the order of 0.5% (plasma levels < 2 ng/ml); harmful effects are therefore unlikely following topical application of this drug. Nevertheless, its transcutaneous passage may be increased in the event of abraded skin or application over an extended area. Several azoles induce anti-androgenic effects [28]. This could cause increased malformation of external genitalia and hypospadias. Numerous studies using rats or mice have investigated the endocrine disrupting potentials of azole fungicides and the observed adverse reproductive outcomes are many and diverse. To date, human data on this subject remains controversial. However, in topical use, considering the pharmacokinetic of these drugs, these effects are not expected.

The EFEMERIS database has the inherent limitations of any reimbursement database, namely the absence of data on self-medi- cation, indication, dosage, drugs prescribed during hospitalisation and compliance. In addition, some risk factors are either miss- ing or are partially missing. For example, we do not know certain risk factors for foetal death such as smoking, obesity, etc. As a result, these variables are not included in the multivariate analyses and residual confounding may be present. The database does not cover the entire population of Haute-Garonne because pregnant women uncovered with general insurance state were not in- cluded (around 16% of the population). However, we can think that this selected population did not impact the risk evaluation of fenticonazole exposure in pregnant women insofar as exposed and unexposed women come from the same population.

Conversely, one of the strengths of our study is that it allows us to study a large cohort over a prolonged period, thus highlighting changes in the prescription and dispensing of drugs for pregnant women over time. It also provides a sufficiently exposed cohort to rule out any significant risk of malformation, for instance. Furthermore, drug prescribing and dispensing data are exhaustive (no memory bias).

Azoles are important agents considering that fungal infections can be very difficult to control or overcome. This study does not report any increased risk of pregnancy termination, prematurity and major congenital malformations and therefore provides reas- surance on the use of topical fenticonazole during pregnancy.

We are grateful to our data providers who made anonymized data available for our research institution: the Haute-Garonne Health Insurance System, the Haute-Garonne Mother and Child Welfare Service and Toulouse University Hospital.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

This study is part of the REproduction Gestation and Reproduction (REGARDS) research programme funded by the French Na- tional Agency for the Safety of Medicines and Health Products (Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament et des Produits de Santé, ANSM). This programme aims to improve drug monitoring in pregnant women in France.

Funding allocation did not impact the study design and conduct, or the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, or the preparation, review and approval of the manuscript.

This publication represents the views of the authors and does not necessarily represent the opinion of the ANSM.

The EFEMERIS cohort was approved by the French Data Protection Authority on 7 April 2005 (authorisation number 05-1140). This study was performed on anonymized patient data.

The women enrolled in the EFEMERIS database were informed of their inclusion and of the potential use of their anonymized data for research purposes. They could oppose the use of their data at any time.

Due to the nature of this research, the study subjects did not agree for their data to be shared publicly – hence supporting data are not available.